Many thanks to everyone who has responded to the news of my mother’s death. I’ve appreciated everyone’s comments, and I was especially intrigued by this one from a long-time commenter.

I would love you to meet my good friend, I’ve spoken of her before, the clairvoyant one.

I would like you to test her objectively, with your atheistic views intact. Ask her to get in touch with your mother.

I should add (for the religious minded amongst your readers) she is a pure Catholic – purest of pure hearts. And I should also add I am almost an expert on the biblical views on visionaries, prophets, and the like. So no-one can argue badly against her without my intervention!

She is likely to get some wisdom and advice from your mother – you can test it for yourself.

I’m challenging you to a duel of sorts, on belief.

Now, I don’t think spirits exist, since no one’s yet presented evidence for them. And the idea of having a medium contact dead relatives is silly. If my Mom’s going to go to the trouble of crossing boundaries of time, space, and matter to give me a message, then I think she’d come to me, and not someone who has to fish around for information, saying “I’m getting the colour red; what does that mean to you?”

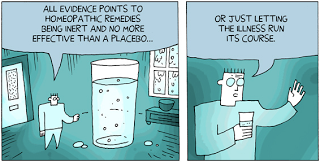

I don’t like what psychics and mediums do. I think they’re either fooling themselves into thinking they can communicate with spirits, or they’re vultures, preying on the grief and desperation of the bereaved. Their techniques are well-known — cold reading is something that you can learn to do. You throw out a lot of suggestions, wait for the subject to feed you information, take credit for the hits, and hope they forget all the misses.

In short, I’m with this guy.

It’s the whole problem of rigour. Going to a medium wouldn’t be a good test for me, since I’m as capable of fooling myself as anyone else. (And maudlin emotionalism, too. After Dad died, I cried watching Blades of Glory, for Pete’s sake. On a plane! It doesn’t take much when you’re in a state.)

With all that in mind, I think the Medium Challenge is a great idea. Even though I don’t believe in spirits and psychic phenomena, I could be wrong, and if we don’t do the experiment, we won’t learn anything new. So I’d like to run the experiment. But it’s going to be a controlled experiment. I want to get not one, but three clairvoyants, psychics, mediums, what have you. As a control, I’ll also need three non-mediums — people who don’t believe in psychic power or readings — doing their best at their own readings.

To make sure I’m not feeding the mediums information, some tight controls will have to be in place. I will be obscured from view by a screen, so the readers won’t be able to read my actions. (It should be all the same to the spirits.) I will only respond to direct questions, and I will only say “yes” and “no”. Other than that, I’ll be very helpful, truthful, and accommodating. The test will be whether the mediums are able to get hits with any greater frequency than the non-mediums, or random chance.

I’d like to video this and turn it into a programme — YouTube at the least, possibly more. Full recordings of all the sessions will be made available via the Internet. And — this is important to me — I’ll be publishing the results no matter what they are, even if they run counter to my current belief. (Or those of the psychics.)

The test needs to be blind, so I won’t know who the mediums or non-mediums are. For this reason, Maureen has kindly agreed to assist in lining up the readings for various nights in November or thereabouts. So if you would like to volunteer as a medium or a non-medium (you-know-who, your friend has priority), please contact her at mediumchallenge@gmail.com.

I still need to work out the particulars of the experiment, so watch this space for the full list of rules and conditions here in comments.

Recent Comments