Daniel Dennett is a philosopher, and author of “Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon”.

His talk was “How to Tell If You’re an Atheist“.

Dennett started out with a discussion of anasognosia, also known as Anton’s Syndrome, or ‘blindness denial’. Sometimes people are struck blind, and they don’t know it. They know something’s wrong; they just don’t know what it is. In the same way, some people might be going through ‘atheism denial’ — being an atheist and not knowing it. I’m not sure it’s helpful to compare atheism and blindness, but it’s Dan Dennett here! so we’re going to cut him some slack.

Dennett is working on the Clergy Project, kind of a research project and support network for pastors who no longer believe. Even though they’ve relinquished their faith, some of these trained ministers may be reluctant to identify as atheists, either because atheism gets a bad rap, or because they’ve invested so much in their religion. It’s their career — and who’s going to hire a 55-year-old theologian? Dennett says these ex-believers are having a hard time finding each other for support, like gay people in the 50s without the gaydar. Dennett gives a clue to spot them, though. The ones who are active in their works are probably the non-believers; they’re trying to atone for their hypocrisy. The ones playing golf still believe.

Dennett explains some of the appeal of atheism: We’re a happy lot, in part because we don’t suffer under a burden of artificial guilt. We feel bad for our misdeeds, but we don’t call them sins. So you might be an atheist if you’re curious about atheists, and yet you’re a little worried about what you might find out about yourself.

Lots of Christians don’t believe that Jesus is the son of a god. In a recent UK poll (commissioned by the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science), the percentage of people describing themselves as Christian has dropped from 72 to 54%. Of those 54% percent, half hadn’t attended a church service in the previous year, 16 percent hadn’t attended in the past ten years, and a further 12 percent had never done so. And only 44% of that “54-percenter” group believed that Jesus is the son of a god. Asks Dennett: Do you believe that Jesus is the literal son of god? If not, you might be an atheist.

What about believing in something divine, like a benign force? Dennett was once asked by a radio host if, despite being an atheist, he didn’t believe in some kind of force that protects us. “Well, yes,” Dennett replied. “Gravity!” If you believe that God is a “concept” that enriches our spirits and enlightens them, then you’re definitely an atheist! Dennett remarked that even he believed that the “concept” of god exists… as a concept. He believes that thousands of concepts of gods exist — but that doesn’t make him a polytheist.

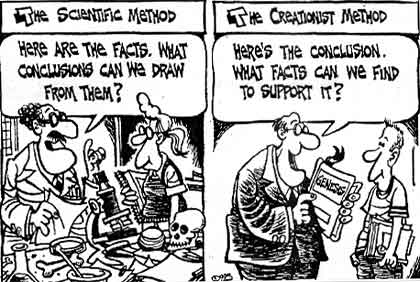

Science is disciplined. It relies on double-blind studies, accurate measurements, and peer review. There’s nothing like this in religion. In fact it’s just the opposite. Dennett cited the phrase “Fake it ’til you make it!” as typical of religion, and mentioned the case of Mother Teresa, who wrote of feeling like god wasn’t there. The fuzziness of religion enables its impenetrable creeds, and in fact relies on them for its survival; creeds that are simple don’t last long. Religion doesn’t survive too much probing, which is why believers think that talking about religion critically is rude — sort of like, “Don’t ask, don’t tell”. Dennett’s response: Don’t ask — Tell!

Technological advances will break down religions. Many of us owe our deconversion in some sense to the Internet, either by exposure to more information, or to the creation of new non-churchy social support networks. The elders of churches will either have to anticipate unwelcome questions from young people, or try and lock the kids away from the technology — and they probably won’t. Eventually, this may lead to religion becoming a semi-transparent myth in our culture, like Santa Claus. Asks Dennett: Wouldn’t it be great if the god myth were semi-transparent like this?

Recent Comments