If you like these cartoons, I have others.

Good Reason

It's okay to be wrong. It's not okay to stay wrong.

Category: post (page 23 of 125)

There’s a primary school in Perth called Edgewater Primary. For 25 years, they forced students to say the “Lord’s Prayer” at school assemblies. Now, they’ve dropped it.

A WEST Australian government school has banned students from reciting the Lord’s Prayer before assembly in response to complaints from parents.

Edgewater Primary School, in Perth’s north, ended the 25-year practice after some parents said it contravened the WA Education Act, which stipulates schools cannot favour one religion over another.

…

“We acknowledge that of the parents who did respond to the survey, many wanted to retain the Lord’s Prayer and it is right that we continue to recite it at culturally appropriate times such as Christmas and Easter, as part of our educational program,” [Edgewater principal Julie Tombs] said in a statement.“However, at this school we have students from a range of backgrounds and it is important to consider all views and not promote one set of religious beliefs and practices over another.”

Good on them. They made the right call.

But some people of faith are foaming about it.

A state primary school in Perth has been inundated with hate mail after deciding to drop the recital of the Lord’s Prayer at assemblies.

The Education Department says the Edgewater Primary School has received letters, emails and abusive phone calls from people around Australia, venting their anger at the decision.

…

The President of the Western Australian Primary Principals’ Association Stephen Breen says the complaints have been vengeful.“We are getting comments like I’ll meet you in the grave, you know real loony stuff,’ he said.

“I don’t want to go on to it too much, but the receptionist is receiving phone calls and then people are slamming down the phone. It’s just gone over the top.”

I can understand that they’re not happy about losing their cultural hegemony, but as Australia and the world become more secular, it’s something they’re going to have to come to terms with.

In the meantime, I’ve written the school an email.

I just wanted to offer my support and tell you that I think your school made the right call. People can practice what religion they like, but it’s not fair for a public school to promote one religion over another. Keeping religion out of schools means that everyone’s religion is on an equal footing, and that’s good for everyone, religious or not. Good work.

If you’d like to convey your support, their email is Edgewater.PS@det.wa.edu.au.

This was exciting to see: Learning the structure of an AIDS-like virus stumped scientists for 15 years. FoldIt gamers cracked it in ten days.

“This is one small piece of the puzzle in being able to help with AIDS,” Firas Khatib, a biochemist at the University of Washington, told me. Khatib is the lead author of a research paper on the project, published today by Nature Structural & Molecular Biology.

The feat, which was accomplished using a collaborative online game called Foldit, is also one giant leap for citizen science — a burgeoning field that enlists Internet users to look for alien planets, decipher ancient texts and do other scientific tasks that sheer computer power can’t accomplish as easily.“People have spatial reasoning skills, something computers are not yet good at,” Seth Cooper, a UW computer scientist who is Foldit’s lead designer and developer, explained in a news release. “Games provide a framework for bringing together the strengths of computers and humans.”

I’ve done work on crowdsourcing annotation in language tasks, so it’s good to see it working in this domain. I love the idea of people putting their heads together and solving problems. For all our computing might, nothing can match human brains on some tasks.

Back in the 1600s, people used auxiliary ‘be‘ + some verbs of motion, where today we’d use ‘have‘.

Shakespeare did it with ‘is fled‘.

LENNOX

‘Tis two or three, my lord, that bring you word

Macduff is fled to England.

And ‘is come‘.

LUCILIUS

He is at hand; and Pindarus is come

To do you salutation from his master.

I thought it would be fun to check it in Google Books Ngram Viewer, and see when ‘has X-en’ became more popular than ‘is X-en’. But you can’t do it with any old verb like ‘make’ — it has to be intransitive. Otherwise, you’re scooping up ‘is made’ constructions like ‘That’s how rubber is made.” Those are still okay now. I want the ones where ‘is X-en’ has been replaced by ‘has X-en’. And the pattern seems particularly common with verbs of motion.

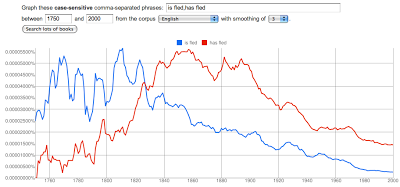

Here’s ‘fled‘. Notice that the crossover happens around 1830ish.

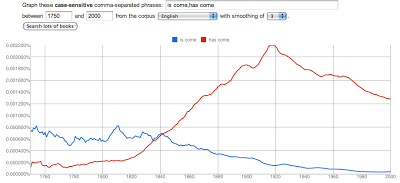

And ‘come‘. They cross over at about the same time: 1840ish.

‘Arrive‘ arrives early — about 1810ish

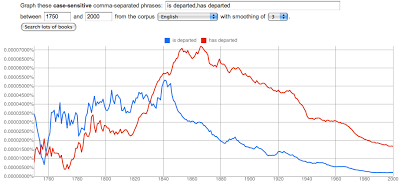

Here’s ‘depart‘, right on the button — 1830 again.

And we see more or less the same pattern with other verbs like land, and become.

What was happening in English in 1800–1840?

When I raised this to the attention of fellow linguist Mark Ellison, he suggested twiddling the ‘Corpus’ menu between ‘British’ and ‘American’. This revealed that the stodgy conservative British books held onto the old usage longer. Perhaps the Americans were at the head of this ‘is – has’ innovation, and the rise we see in the corpus was partially due to more books being published in the Colonies.

I’ll have to do some looking around to see if anyone knows more about it. Luckily, I have two experts on present perfect in my very own department. Meanwhile, I think it’s cool that I can search centuries of language patterns in seconds.

France, what am I going to do with you? You know I love you, right? because you’re so cool, and you have a great language and everything. But I’m all torn about this.

Paris ban on Muslim street prayers comes into effect

A ban on saying prayers in the street, a practice by French Muslims unable to find space in mosques, has come into effect in the capital, Paris.

Interior Minister Claude Gueant has offered believers the use of a disused fire brigade barracks instead.

The phenomenon of street prayers, which see Muslims spreading mats on footpaths, became a political issue after far right protests.

Sure, they’re praying, which is stupid and useless. And it is unsightly having people clogging the streets like this.

I actually feel kind of embarrassed for those people, groveling around like that. But as obnoxious as public prayer is, banning it will heighten tension, and turn an annoying (but relatively harmless) public performance into a political football — or even an opportunity for civil disobedience. That brings in the sympathy. Shoot, even I’d be sympathetic to some non-violent civil disobedience on a issue of conscience.

There must some way of fixing this without some ad hoc law seemingly targeting Muslims. If all these people praying in the street is a problem, how about prosecuting it using an existing law? How about obstructing a footpath? Blocking traffic? Noise pollution? Littering?

Okay, that was reaching, but I’m trying to help here.

Check out this short film “Doubt” from the Climate Reality Project.

What they did to obscure the facts about smoking is what they’re doing now to muddy the waters about climate change: Manufacture enough phony controversy and confusion to get people to ignore the science.

And according to the film, “they” are the same people in both cases.

I’m a bit of an ethical utilitarian; that is, I generally think an action is good if it has good effects. I can see some problems with it. Since we can’t always predict the effects of our actions, utilitarianism works best in retrospect. And defining ‘good’ has its own problems, but I know it when I see it.

But I like to hear the other side. So, for the second time in two days, I went to hear a Christian have a bash at a competing philosophy. I wasn’t expecting to hear how Christianity improves on utilitarianism. They never seem to do that. They just say God is wonderful. But I hoped to get a better idea of other views on ethics.

The speaker mentioned the above problems with utilitarianism, all of which I would have happily conceded. I could have done without the straw men, though. (Did you know that utilitarianism can lead to gulags and gambling, if you define ‘good’ stupidly enough?)

So what was his great idea for ethical behaviour? It’s quite an eye-opener: An action is good if god says it is. I asked him how he could know what god wants, when believers have come to many different conclusions about that. His answer: He reads the Bible and decides. That’s unlikely to lead to any ambiguity.

At the end of the presentation, I was unconvinced that his system of ethics held any advantages. Sure, he was against gambling and gulags, but a utilitarian could be against both of those things. The difference is that they’d be against it because it was bad for people, and he’d be against it because a god said so. I had a Socratic realisation that I knew one thing more than he did: I knew that my ethical system was made by humans. His system of ethics was made by humans, too, but he didn’t know that. He thought that his system of ethics was handed down by the supreme creator of the universe. I suspect that would make him less capable of compromise.

Despite the presentation, I was quite encouraged by the Christians I met. They asked some good (and in some cases, thorny) questions, including a brief touch on Euthyphro’s dilemma. Also, the ones I met were actually in the process of reading Dawkins and Dennett. Are atheists reading Eagleton and Plantinga? Ugh, no thank you. If we tried to reciprocate, the Christians would be getting the better end of that deal. Still, I respect their curiosity and willingness to check out the other side.

© 2025 Good Reason

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Recent Comments