Leslie Cannold is a writer, activist, and the author of “The Book of Rachel”. Her talk: Separating Church and State: A Call to Action.

It’s one of those funny paradoxes that Americans seem super-religious, when their constitution has provisions for the separation of church and state — and what’s more important, that separation gets upheld in court. Australia, however, allows lots of religious stuff past the legal barriers — and Australians are largely secular. The net effect is that Australia does not really achieve a separation of church and state.

Cannold compared the relevant bits of each country’s constitution. Let’s start with Australia:

Section 116: The Commonwealth shall not make any law for establishing any religion, or for imposing any religious observance, or for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion, and no religious test shall be required as a qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth.

And the USA:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…

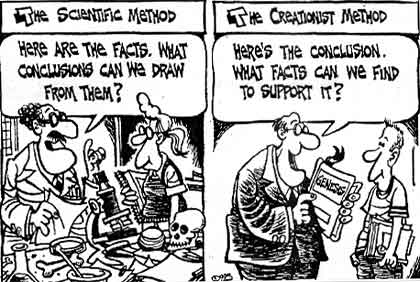

Both texts read about the same. The difference is that of implementation. In USA, courts have a tradition of “reading it up”, so that an action is prohibited unless it’s explicitly okay. In Australia, they “read it down”, so that it’s okay unless it’s explicitly prohibited. That means a lot of religious stuff gets in.

The difference between the two methods of implementation shows up in two landmark cases, both of which involved the role of the government in promoting religion in schools: McCollum v Board of Education (USA, 1948)

“For the First Amendment rests upon the premise that both religion and government can best work to achieve their lofty aims if each is left free from the other within its respective sphere. Or, as we said in the Everson case, the First Amendment had erected a wall between Church and State which must be kept high and impregnable.”

and The Dog’s Case (Australia, 1981), in which one Justice said:

[Section 116] cannot readily be viewed as the repository of some broad statement of the principle concerning the separation of church and state from which may be distilled the detailed consequences of such separation.

What this means is that Australian taxpayers pay to promote religions:

- religious festivals (millions of dollars for World Youth Day)

- canonisations ($1.5 million in the case of Mary McKillop)

- tax breaks for churches

- private schools

- and exposing kids to religion via chaplains

Cannold actually has no objection to Religious Education taught by teachers. However, at the moment we have a situation where access to high school students is thrown open to what can only be described as evangelists. Here’s the head of Access Ministries:

“There is enormous amount of christian ministry going on in our schools, both at state level and at at national level, both at government and non-government schools, but we must ask how much of that ministry is actually resulting in christian conversion and discipleship growing”

“Our Federal and State Governments allow us to take the Christian faith into schools. We need to go and make disciples.”

In Cannold’s view, Australia is a soft theocracy. Politicians feign religiosity because they think it will get them votes. Our Prime Minister (who Fiona Patten calls a “non-practicing atheist“) has given religions everything they’ve wanted.

So what can we do?

Cannold emphasises that “we” includes the non-faith community and some religious believers who can’t stand this trend and who consider faith a private matter. We need to find them and form coalitions.

Here are some simple suggestions from Cannold.

Join the Facebook group for Australians for Separation of Church & State

Help with the Australian University Freethought Alliance.

Donate to Ron Williams. He’s single-handedly mounting a challenge against the chaplaincy, and the legal costs are climbing. Throw him some dough.

Engage in web-based advocacy

Build alliances with teachers. There are teachers who agree that scripture shouldn’t be taught in school, but after school. Opt-in, not opt-out.

And foremost — we need to admit that we do not have a secular state in Australia. We think of ourselves as secular and non-religious, and we are. But we’re also kind of conflict-averse, and we need to stop that.

Recent Comments