Scott Murphy is running for Congress in District 20 in the great state of New York. Not only is he a Democrat, and therefore one of the good guys, his campaign clearly has very discriminating taste.

Download the Daniel font for free from dafont.com.

Scott Murphy is running for Congress in District 20 in the great state of New York. Not only is he a Democrat, and therefore one of the good guys, his campaign clearly has very discriminating taste.

Download the Daniel font for free from dafont.com.

God won’t heal amputees, but science sure will.

Amanda Kitts lost her left arm in a car accident three years ago, but these days she plays football with her 12-year-old son, and changes diapers and bearhugs children at the three Kiddie Cottage day care centers she owns in Knoxville, Tenn.

Ms. Kitts, 40, does this all with a new kind of artificial arm that moves more easily than other devices and that she can control by using only her thoughts.

“I’m able to move my hand, wrist and elbow all at the same time,” she said. “You think, and then your muscles move.”

…

The technique, called targeted muscle reinnervation, involves taking the nerves that remain after an arm is amputated and connecting them to another muscle in the body, often in the chest. Electrodes are placed over the chest muscles, acting as antennae. When the person wants to move the arm, the brain sends signals that first contract the chest muscles, which send an electrical signal to the prosthetic arm, instructing it to move. The process requires no more conscious effort than it would for a person who has a natural arm.

You really ought to take a look at the video. Amazing.

I think it’d be tricky to use the arm and fingers because of the lack of tactile feedback. You’d have to look at the object you’re holding to make sure you had it securely and weren’t squishing it. Maybe in future you’d be able to ‘feel’ the item you’re grasping by some kind of neural feedback.

When some new age creep wants to talk about the shortcomings of Western medicine, they’ll get a face full of this article from me.

Cheney people are having a non-stop virtual high school reunion on Facebook. I’m communicating with people that I haven’t seen in 25 years. What a great way to bring people back into your life!

One day not long ago, a guy from my old high school sent me a friend request. To preserve his anonymity, I’ll call him ‘Barry’. Barry was never very popular in school, but I couldn’t say exactly why. He was actually a pretty decent guy, as I found out when I talked to him at a chance supermarket meeting a couple of years after graduation. But not the sort of guy you’d hang out with. You’d say hi in the halls. Maybe if you were socially conscious, you’d hope no one was looking, but you’d feel guilty about it. A very high school feeling.

So when I got Barry’s friend request, I felt that old reflex. It was like Barry had come up to me and said, “Hey, guys! What are you doing?” A brief thought: would people see him on my friend list? Then I came to myself and felt ashamed of my reaction. What was this, high school all over again? I had forgotten he existed for the better part of three decades, but he remembered me, and now here he was, asking for me to be… his friend. And all it required of me was to click.

Had I learned nothing about common human decency in the last 25 years? We weren’t kids anymore — especially not Barry, by the looks of his Facebook photo. But what did that matter? I’m past all that stuff. Yes, Barry, yes! I will be your friend! And just that simply, the pettiness of adolescence was erased in one virtuous act. If Barry had only one friend, it would be me. Even if I was just a Facebook friend.

The next day, Facebook sent me an email. I had a pillow fight request. Barry had somehow hit me with the Eiffel Tower. I ignore these requests from everyone, and so I ignored it from Barry. Over the next two days, Barry hit me with four more objects, and invited me to play backgammon and Scrabulous. I was busy. I changed my email notification preferences.

I don’t hit the ‘Book often, so the next time I logged on, I found that I had been kidnapped twelve times, each time by Barry.

I tried not to feel conflicted as I clicked the ‘Ignore all requests from this friend’ button. Stupid Facebook, bringing people back into my life. Why couldn’t they stay in the past where they belonged? It was high school, all over again.

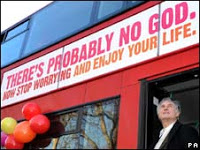

The main charges people made against the London atheist bus ad was:

The main charges people made against the London atheist bus ad was:

1) It made claims that broke rules of substantiation and truthfulness, since the ad offered no evidence for god’s non-existence.

2) The ad was offensive.

I find both complaints questionable. The inclusion of ‘probably’ helps to tone down the claim, and as for offense, I found the ad quite positive in tone. Maybe people found it offensive that anyone would express a belief they disagreed in.

What are we to make, however, of the next round of bus ads from the believers?

The first one libels a group of people, and the second has factual problems! Both are far guiltier of the charges than the original ad itself.

If they’re so sure that there’s ‘definitely’ a god, let’s see their evidence. They don’t know their bible either; calling someone a fool puts you in danger of hellfire. Name-calling is name-calling, even if it’s biblical.

I can’t say I mind the Christian ads though. A vigorous debate is always healthy, and these ads will probably just make people think of the original.

The Problem of Evil was never a problem for me in my believing days. I always thought it was a pretty weak argument. So bad things happen to good people. It’s too bad, but why should god come running in to save us from every bad thing that might happen? How would we have free will if we couldn’t suffer the consequences of our actions? Don’t murderers have free will too? How would we have good if we didn’t have evil? And god’s intervention would ironically prove he existed, so how would we have faith in him? Besides, life isn’t so very long when we compare it to an eternity in god’s presence. It was all a case of putting unrealistic expectations on god, who after all probably had good reasons to allow kittens to drown, children to be abused, neglected, and murdered, bombs to fall, hurricanes to destroy, viruses to kill and maim, and all the other wonderful things that work towards god’s greater glory.

And so I would walk away from the Problem of Evil, dusting off my hands and whistling, thinking the matter settled. Well done, me. What I see now was that I accepted those answers not because they were all that great, but because they allowed me to put my cognitive dissonance back to sleep so I could stay in The Bubble and keep believing for yet another week.

Of course, the temptation to accept bad ideas because you like them still holds whether you’re a theist or an atheist. So I’ve been wary of throwing myself into the PoE because, until recently, I still thought it was a weak argument. This document changed my mind: The Tale of the Twelve Officers, by Mark I. Vuletic.

It was, of course, sad to hear that Ms. K had been slowly raped and murdered by a common thug over the course of one hour and fifty-five minutes; but when I found out that the ordeal had taken place in plain sight of twelve fully-armed off-duty police officers, who ignored her terrified cries for help, and instead just watched until the act was carried to its gruesome end, I found myself facing a personal crisis. You see, the officers had all been very close friends of mine, but now I found my trust in them shaken to its core. Fortunately, I was able to talk with them afterwards, and ask them how they could have stood by and done nothing when they could so easily have saved Ms. K.

Each officer has a rationalisation for their failure to act, and what do you know — all my old friends are here! Wonderful ways to explain why an all-good and omniscient god would fail to do what any normal, compassionate, sinful human being would do in the same situation.

How do their answers sit with you, whether theist or non?

Good call from U of M:

The University of Michigan-Flint is the latest school in the state to accept American Sign Language as a foreign language.

The Flint Journal reported Friday the decision follows years of effort by Jill Maxwell of [sic] for the designation. Maxwell graduated in December and substitute teaches at the Michigan School for the Deaf in Flint.

The 32-year-old DeWitt resident argued it was discriminatory not to accept ASL for second language requirements.

Yes, ASL is a foreign language to English speakers. It has its origins in spoken English, but it’s grown and changed since then, and (most importantly) it’s not mutually intelligible with English.

D.J. Trela, dean of UM-Flint’s College of Arts and Sciences, says faculty studied the issue for 14 months.

I hope they spent the 14 months hashing out the procedural details, and not just wondering if it was actually a different language. They could have asked a linguist.

My head of department asked the postgrads who teach classes to give some advice to new teachers. Here’s what I wrote. I think it applies to areas of teaching beyond linguistics.

= – = – = – = – = – = – = – = – = – = – = – = – = – = – = – =

Here are some ideas to think about, though obviously everyone will have to do things their own way.

• Ask yourself: Why do you like linguistics? You’re probably in this area because you think it’s sort of cool. And it is! So show your students what you love about linguistics. They will pick up on your enthusiasm.

• Try and remember one teacher that you liked. What did they do? Why did you like them? For me, I remember Marge Foland, my drama teacher. She was fun and ‘sparky’, with a zany sense of humour. She expected great work from us, and we were happy to give it. I don’t teach just like she did because I’m a different person, but I do find that that kind of style works for me. Whatever your teacher did that clicks with you is an indicator of a teaching style that you’ll probably do well at.

• Teaching is a lot like parenting. You have to convey expectations clearly to your students, give them nurturing feedback, and dish out consequences when they need it. (Warm and fuzzy, not cold and prickly.) Also, you must like your students.

• People learn by doing things. Try and take every opportunity to present students with real live data, and have them deal with it. Focus on the principle you’re trying to reinforce. Often what will happen is that they’ll run up against the limits of their knowledge, and struggle to find a solution. Then they’re ready for you, the experienced one, to provide some suggestions for moving ahead.

• No one expects you to be infallible, just reasonably well-read and well-informed. A great thing to say is “I don’t know” and the next thing you should always say after that is “How could we find out?” And it’s not bad to follow that up with “If I had to make a guess, I’d say… And the reason I say that is…” When you say these things, you’re preparing them to solve their own problems.

• Let them talk to each other and contribute their unique experiences to the class. I do a lot of small group discussion in tutorials. When I’m doing all the talking in the tutorial, I know something’s wrong. Step back and let them work through the issues without you. You may worry that they’ll reinforce each others’ mistakes, but that doesn’t usually happen. Groups of people are smarter than their smartest member, so they’ve got a better chance of getting it right. Sometimes they come up with ideas I haven’t thought of. And they get a chance to contribute, so they’re building the class.

• Always have a contingency plan. Activities run short or sometimes just don’t work, and you’ll need to have something else to do. Even having a few discussion questions up your sleeve can save the day. Don’t be afraid to toss the lesson plan and have a discussion they’re interested in, if the tutorial goes that way. Let them drive. Some of the best tutorials are like that.

• Teach the scientific method. Our data comes from the physical world. We develop testable and falsifiable hypotheses to explain the data, and if the hypotheses don’t correspond to the facts, we modify or dump them. We have many perceptual filters and biases that prevent us from seeing things clearly, and we have tools like statistics to help us avoid these traps. Find out about them. Use issues in linguistics to teach the basics of critical thinking, including the virtues of open-mindedness and skepticism. Avoid holy wars. By teaching students the scientific method, we’re not just doing good linguistics, we’re building a populace that is better equipped to live in the world, even after they’ve forgotten all the things we’ve presented.

Last week was taken up by a happy event: Ms Perfect and I moved into our new home. That meant getting all the furniture in, tracking down the right hedge trimmer (so as not to obscure the white picket fence), and getting the utilities hooked up. Now the Internet Drought is over, and I’m back online.

We here at Good Reason like to keep up with everything typographical, so when we found the Atheist Bus typeface, it was too good not to share. Here it is: Dirty Headline, the very same font used on atheist buses in England (and atheist t-shirts elsewhere), downloadable for free thanks to dafont.com.

Making your own atheist slogans is now a simple matter. Maybe you like the current one, but you think it lacks a little punch. Why not try pumping up the volume?

Now that’s a spicy meatball.

Did anyone notice this fine piece of legislation? South Carolina Senator Robert Ford wants to make swearing a felony.

Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina:

SECTION 1. Article 3, Chapter 15, Title 16 of the 1976 Code is amended by adding:

“Section 16-15-370. (A) It is unlawful for a person in a public forum or place of public accommodation wilfully and knowingly to publish orally or in writing, exhibit, or otherwise make available material containing words, language, or actions of a profane, vulgar, lewd, lascivious, or indecent nature.

What’s the penalty? Get this:

(B) A person who violates the provisions of this section is guilty of a felony and, upon conviction, must be fined not more than five thousand dollars or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.”

Takes me back to the good old days of Puritan America, where blasphemy could get you whipped, your forehead branded with a ‘B’, or your tongue bored through with a hot iron. For repeat offenses, you could be killed. And remember that blasphemy could be swearing, or simply being an atheist.

In 1699 a Virginia statute was designed to eliminate “horrid and Atheistic principles greatly tending to the dishonor of Almighty God . . . “Blasphemers might deny God or the holy Trinity, declare that there are more than one God, or worship another god or goddess.

Dark days.

Hey, is ‘piss’ vulgar? Because I have a book that Mr Ford might like to prosecute.

Latter-day Saints believe that their church is the Only True Church on the earth. That’s not such a drastic claim. Even though not every religion comes out and says it, most religions would say that their system (if not their own particular denomination) is true and all other are in some sense less true.

I was talking to The Priest about this, and I asked him, “Let’s say I told you that Apollo pulled the sun across the sky in a chariot. Would you accept my claim?”

He had to allow that he wouldn’t.

“Why not?” I asked. “On what basis would you reject my religion and accept yours? Or what about Muslims or Hindus with their claims?”

His answer was that he’d read and studied things, and the Holy Ghost had confirmed to him (via those wonderful feelings and experiences) that his religion was true.

“Well, they’ve read and studied, too!” I said. “And they have strong feelings that their religion is true. Are your feelings somehow more valid than theirs?”

There isn’t really a good answer to that, and to his credit he didn’t try to invent one. But imagine the cheek of taking that kind of approach!

When Mormons claim to have the One True Religion, they don’t really mean to be arrogant, truly. They sometimes allow that all religions have some truth (oh, what a generous admission), but they have more. Well, that would be all right, if they had better evidence than flimsy feelings, but they do not. So for churches that use emotions as evidence, that means that their proof is the intensity or the frequency or the persuasive power of the feelings they have. Other people in deadened and benighted religions may have spiritual feelings, sure, but they’re just not as real or powerful as their feelings. Their feelings just aren’t as valid.

That conversation was an eye-opener to me. I never realised how breathtakingly arrogant that view is, but it is. And it’s not exclusive to Mormons. It’s indulged in by every religious believer who says that their nebulous claims trump other people’s nebulous claims.

NB: The Priest is not a real person. He’s an amalgam of many religious people I’ve spoken with. I only write down a conversation with “the Priest” after I’ve heard the same claims from at least three different people. As a result, the dialogue is almost entirely made up, in order to make myself sound smart. Or it could be 100% accurate. I forget.

© 2024 Good Reason

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Recent Comments