Religions are in the business of providing emotional comfort (among other things), and after 11/9/1, Americans’ sense of stability was rocked. I think this played out in a predictable way for Mormons.

I visited my US home ward in late 2001, and it was the strangest thing: I’d never heard so many references to Satan before. Naturally, when people feel like events are out of their hands (what’s known as an ‘external locus of control’), they develop superstitions, and here it was unseen malevolent agents. I saw something else on that visit that I’d never seen before: In Priesthood Meeting, they’d developed the habit of reciting their ‘group values’ in unison, chanting a sort of ‘we believe’ mantra. Even as a believer, it struck me that here was a group of people too frightened to think.

From a look at this WaPo column, Mormon president Thomas Monson sure misses that time.

There was, as many have noted, a remarkable surge of faith following the tragedy. People across the United States rediscovered the need for God and turned to Him for solace and understanding. Comfortable times were shattered. We felt the great unsteadiness of life and reached for the great steadiness of our Father in Heaven. And, as ever, we found it. Americans of all faiths came together in a remarkable way.

And the bottom line couldn’t have been better.

Side note: what’s with the capital H on ‘Him’? I haven’t seen that in Church publications since the 1920s.

Sadly, it seems that much of that renewal of faith has waned in the years that have followed. Healing has come with time, but so has indifference.

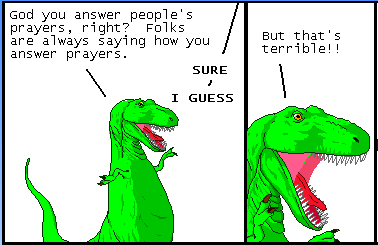

Isn’t it too bad that we don’t have more horrible tragedies to turn our hearts to god? Darned if Monson doesn’t feel some nostalgia for that time of national agony. What a ghoul.

Whether it is the best of times or the worst, He is with us. He has promised us that this will never change.

But we are less faithful than He is. By nature we are vain, frail, and foolish. We sometimes neglect God.

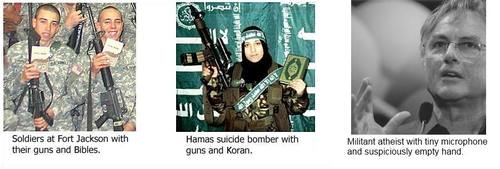

Then we’re even, because God was more than a little neglectful on that day. He failed to save the lives of 3,000 people, but left instead a steel cross. You know, just to let us know he’s there, thinking about us.

If you object to this, saying that ‘super-hero’ isn’t part of god’s job description, consider: What would you have done if you’d had the knowledge of what was about to happen that day, and the ability to do anything? Well, god had all that, and still failed to do what you — a normal human, with all your goods and bads — would have done. Why do people say that god is good?

Mormons talk interminably about what they call the ‘pride cycle’: People get prosperous and prideful, they forget god, then god (that sicko) burns them up in fires, buries their cities in earthquakes, or sinks them into the sea (and that was gentle Jesus, BTW). Then the people remember to grovel sufficiently before him, and he prospers them. Because it’s all about him.

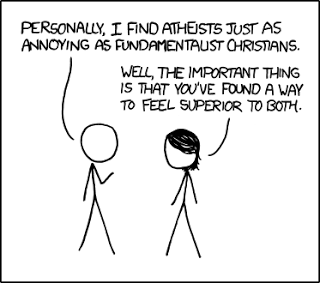

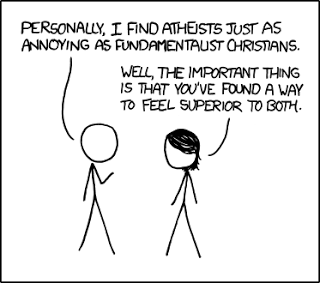

One could rewrite the narrative thus: Tragedies happen, and the feeling of vulnerability drives people into authoritarian religions. But life goes on, and people stop feeling frightened, at which point they abandon superstition, becoming secular or at least joining liberal churches. Until the next tragedy. Rinse, repeat.

Small wonder, then, that Monson is banging the drum for a more godly society. The vacuum cleaner salesman wants everyone to buy vacuum cleaners, and the god salesman… you get the picture. It’s just business.

Recent Comments