Today on campus, there was a Christian Union talk about atheism, entitled ‘Why I am not an atheist‘. I can’t stay away if atheism is being discussed, and while they’re usually well-read on Dawkins et al. and give a good critique of the Gnu Atheism, they don’t always apply the same critical eye to their own faith. I was hoping the speaker would explain how Christianity improves on atheism, and in this I was (inevitably) disappointed.

A guy named Rory was the presenter. He was a good speaker — enjoyable to listen to, funny at the right times. His main reasons for being a Christian and not an atheist were:

- He had no compelling reason to doubt his ‘sense’ that a god exists. It seemed to me that if he’d been born elsewhere and -when, he’d have no compelling reason to doubt his sense that Odin or Vashti exists. Beliefs are true to the extent that they are supported by evidence, not hunches.

- The Christian world-view ‘resonated’ with his experiences. But people who have different world-views also find that their experiences ‘resonate’, whatever that means. Our experiences don’t always mean what we think they mean.

- He found it satisfying to have someone to thank (after thanking people). I understand that — I feel grateful to the people in my life, and once I’ve thanked them, I like to pour my effort into making things better for them through service.

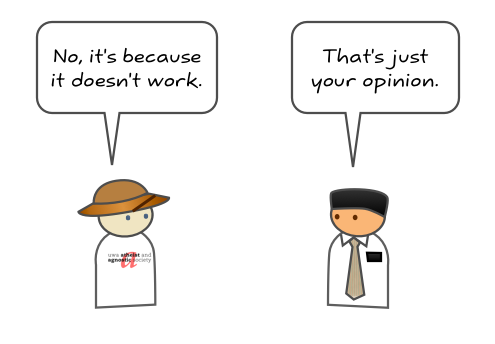

- Finally, he found it hard, within an atheistic worldview, to account for things that are wrong in the world. I don’t know why he decided to press that point. Why would he use this as a strike against atheism, when this is actually much harder to explain from a Christian perspective? In question time, I mentioned that it was very easy for atheists to explain evil in the world — people decide to do things that harm people. But it’s very difficult for believers in an all-powerful, good god to explain why bad things happen. There’s a whole branch of theology (called theodicy) dedicated to trying to explain this very thing, yet the Problem of Evil remains. But Rory couldn’t quite get why atheists would see a thing as ‘evil’ outside some kind of ‘god’ frame. Unfortunately, we had to move on before full understanding could be achieved. Rory — if you’re out there, let’s continue this, because I’d like to understand your view.

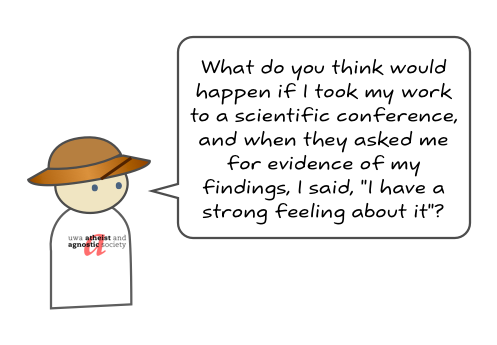

I did ask one other question, though. His last point in the presentation was that he found it naïve to think that science was the ‘only way of knowing’ something. Now, I’ve heard people say that there are other ways of knowing, and when I ask them what they are, they invariably respond with something that is… not a way of knowing.

In response, Rory mentioned Dawkins’ letter to his daughter, in which he wrote that tradition, authority, and revelation are bad reasons for believing something. But Rory thought that these were okay reasons to believe something, part of this complete scientific breakfast. He also mentioned intuition as something that was important in finding truth.

I explained that intuition was important — say, in coming up with a hypothesis — but intuition is not a way of knowing. If someone has an intuition about something, they do not know that that thing is true. It appeared that he was confusing ‘how you get an idea’ with ‘knowing that the idea is true’, which is a rather serious mistake.

So I want to say this very clearly: The way to know something is by empirical observation. That is the only way. (And even when we’ve observed something, it still might be wrong! Which is why replicable observation is so important.) There are no other ways of knowing. Not tradition — many traditions have turned out to be wrong. Not authority — authorities can be wrong. Not revelation — you don’t know the source of a supposedly supernatural revelation. It could be all in your head. Science — systematic, reproducible, empirical observation — is the only way of knowing.

If you think you have another way of knowing, leave it in comments, and we’ll have a look.

Recent Comments