I had an exchange with a Mormon friend a little while ago. His interesting but ultimately vacuous argument went something like this:

“You say you rely on evidence for the things you believe. But you’re only relying on physical, tangible evidence. You’re not relying on spiritual evidence, and so you’re only getting part of the picture. I’m using the full range of evidence available to us.”

My response is two-fold:

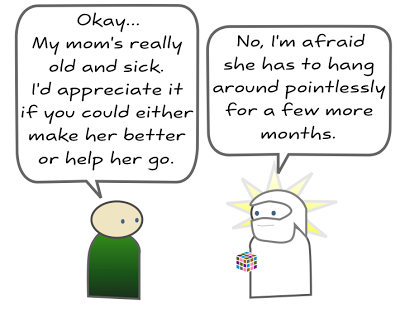

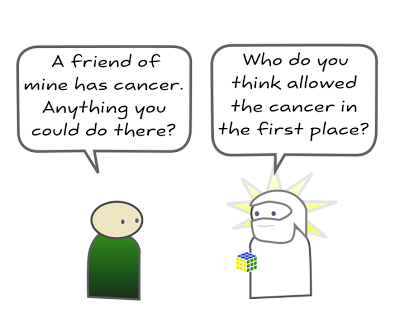

1) There is no empirical evidence for the claims of religion, including the existence of a god, the reality of an afterlife, or various details such as a Tower of Babel, gold plates, or Lamanites. The key doctrines of religious belief systems are either unsupported by evidence, or refuted by evidence. (Occasionally a religion will teach a principle that turns out to be valid — the Mormon prohibition on smoking seems worthwhile on its face — but these are things that could have occured to someone without requiring revelation.)

2) What my friend was calling ‘spiritual evidence’ is actually not good evidence at all. I think he was referring to something Mormons call ‘personal revelation’ — messages that people think they’re getting through prayer.

This is not a good way of finding out what’s true. How you feel about a proposition has nothing to do with whether it’s true or not. You can feel great about things that are completely false. Yet this method is at the very heart of the Mormon conversion experience — and other forms of Christianity also place an emphasis on emotional reasoning.

Let’s take a step back and see how this plays out in LDS missionary work.

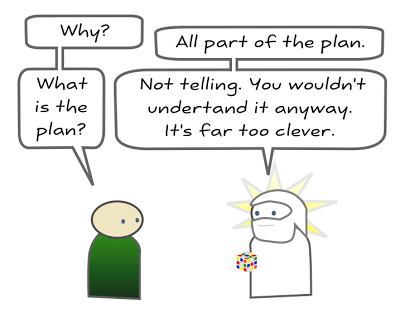

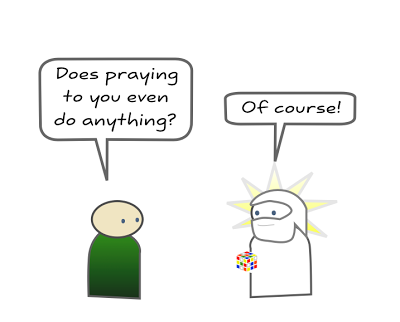

LDS missionaries encourage investigators to ‘experiment upon the word‘. And the experiment that they propose is that you can pray and receive answers about the truth of their message telepathically from a god.

They rely on a scripture from the Book of Mormon, Moroni 10:4, which says to ask God, and the Holy Ghost will tell you if it’s true. By doing this, the missionaries commit the fallacy of begging the question — they claim that a god will tell you that the religion is true, but the existence of said god is the very premise under consideration.

And how does the Holy Spirit let you know?

But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, longsuffering, gentleness, goodness, faith,

Meekness, temperance: against such there is no law.

That’s a pretty big list of fruits. Almost any feeling could qualify as a confirmation, especially if that’s the conclusion you want to come to, and you wouldn’t be asking if you didn’t have at least a glimmer of hope that it was true.

It should be obvious that this is not a real scientific experiment, and not just because it falls back on supernatural explanations.

- Scientific experiments use evidence that is empirical — involving sense data that could be observed by anyone

- Experiments try and control for bias

- Experiments are replicable — anyone can repeat the experiment, and they should get about the same result. Ideas are verified by multiple points of view.

But so-called personal revelation doesn’t follow these controls.

- Your feelings can’t be directly observed by other people. That makes it impossible to evaluate someone else’s religious claims, and that means that religious people have to ‘agree to disagree’ when they get conflicting revelations.

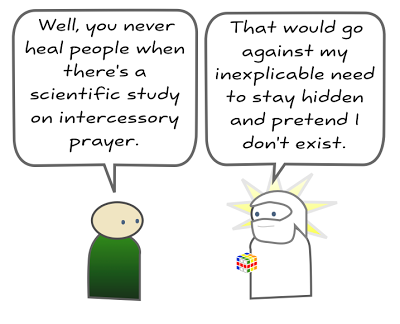

- There’s no way to tell whether the feeling you’re getting is a real live revelation from a god, something from your own mind, or (worse) a temptation from an evil spirit, if you go for that. Or Zeus, Krishna, or the Flying Spaghetti Monster. It’s easy to distinguish between two competing natural claims, but it’s impossible to distinguish between two competing supernatural claims.

- A scientific experiment attempts to control for bias, but here, the missionaries are subtlely biasing their subjects by telling them what they should expect to feel. It’s sort of like when you’re playing records backwards for satanic messages — it’s hard to tell what the message is until someone gives you the words.

- The goalposts for this test are defined very vaguely and can be shifted. A confirmation can be ginned up out of the most meager of subjective data — or no data at all. Many are the members who ask for a revelation, get none, and continue in the church anyway, figuring that if they have real faith, they don’t need a spiritual confirmation. It’s a hit if you have good feelings, and hit if you don’t.

- In a real experiment, we would try to account for both positive and negative results. But here, no attempt is made to add negative results to the sample. People who report a positive result show up in church, but people who get no result don’t, and are effectively deleted from the sample. In fact, if someone doesn’t get a revelation, it’s assumed that they are to blame for not being ‘sincere’ or trying hard enough. They are encouraged to repeat the test until they get a result that the experimenter will like.

- Worse still, once someone is convinced that they’ve received a message from a god, Latter-day Saints then make a series of logical leaps to show that the whole church is true, from the Book of Mormon to Joseph Smith to Thomas Monson and beyond. All from good feelings and not from anything solid.

Not everyone is convinced by this test, but the church doesn’t need everyone to buy it — just enough people to keep the system going. And I can tell you from personal experience that when you think you’ve been touched by the divine, it can be very difficult to balance that against real evidence. No good evidence is going to come out of this kind of test. This is not a valid experiment. It is a recipe for self-deception. It is just asking to be fooled.

Recent Comments