Two articles crossed my screen today, and they’re a great example of the divide between rational thought and superstition.

They’re both about the gun tragedy at Sandy Hook, and the first one is written by a Catholic priest.

Now, believers in the Christian god have a bit of explaining to do when horrible things happen. That’s because they claim there’s a god who’s good, loving, and all-powerful, but who somehow fails to prevent evil things from happening. So after a tragedy, a reasonable question is: where was he? Is he really all that good if he has the power to prevent grade-school massacres, yet chooses not to? Here’s the theologian’s answer:

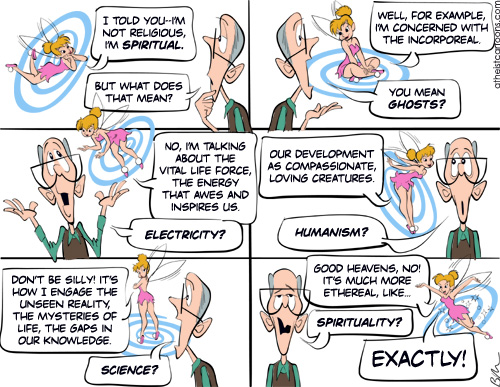

The truest answer is: I don’t know. I have theological training to help me to offer some way to account for the unexplainable. But the questions linger.

Well, that’s a bit pathetic. He doesn’t know? All that theological training, and he can’t answer a question that belongs in his discipline?

Seriously, read it; it doesn’t give any more than a shrug. And it’s not just this writer. This is literally the best they’ve got. (Oh, there are other religion guys out there who do claim to know, but their answers are so morally callous as to be not worth repeating.)

I will never satisfactorily answer the question “Why?” because no matter what response I give, it will always fall short. What I do know is that an unconditionally loving presence soothes broken hearts, binds up wounds, and renews us in life. This is a gift that we can all give, particularly to the suffering. When this gift is given, God’s love is present and Christmas happens daily.

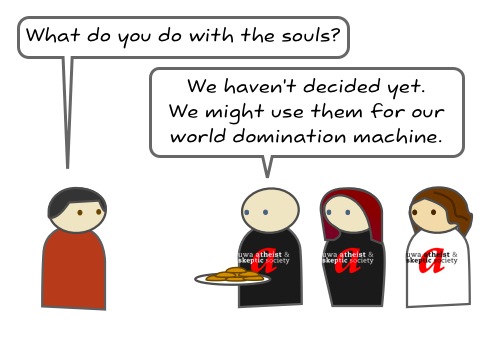

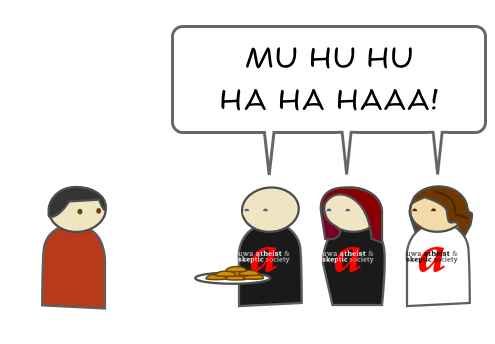

Great, so if you help others, it’s actually god’s love; not yours. (Hat tip to Stephanie for this thought.) And why would ‘soothing’ be a consolation? I’d exchange buckets of after-the-fact soothing in order to not have had that tragedy happen. Who wouldn’t? What’s wrong with this guy? But all we’re left with is: I don’t know.

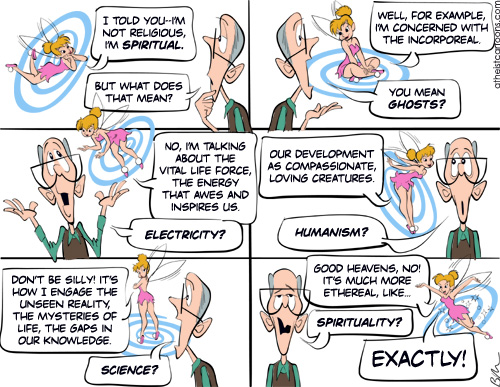

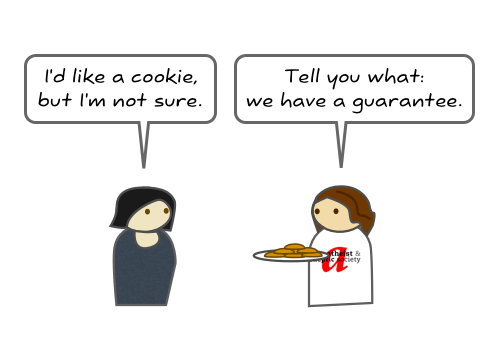

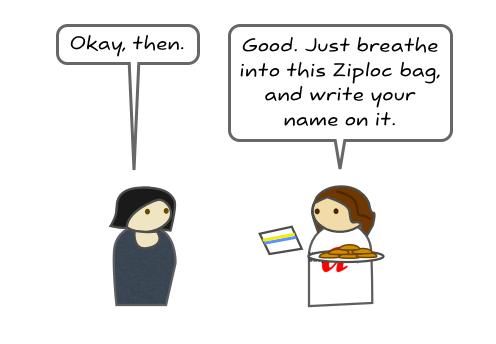

It’s good to admit when you don’t know something, but if you have no way of finding out, and no way of telling whether your answers are good ones, you have a bit of a fucking methodological problem. And this is a sad sign of the inadequacy of supernatural thinking. See, I do science because science is good at scientific questions. People may say that science isn’t good at moral questions or spiritual questions, and we can argue that. (My answer is that it does just as well as anything else.) But by gum, science is good for doing science.

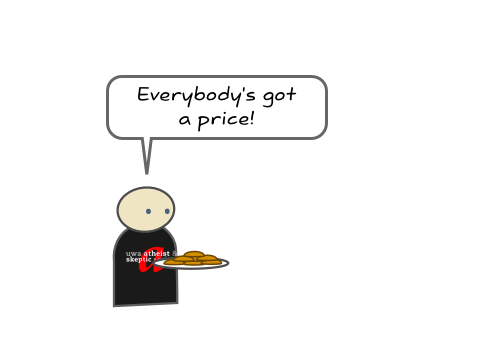

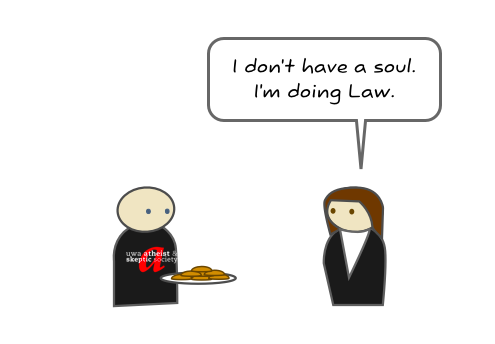

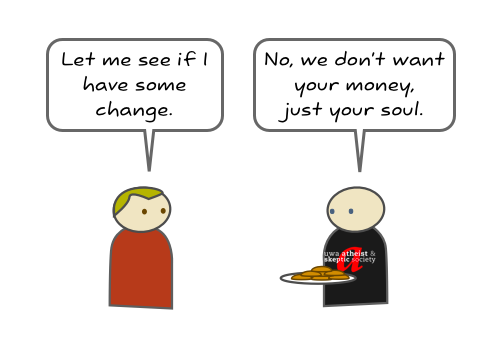

Spiritual reasoning, on the other hand, isn’t good at answering scientific questions, but it’s also terrible at answering spiritual questions. It’s incompetent within its own domain. It is a shitty way of reasoning. Pardon my language, but spirituality/religion/supernaturalism has one job, and it sucks at it, and this incompetence makes me angry, especially when we have people telling us that it has the answers to life’s great questions, and then when it comes down to it, all that its professionals can tell us is “We don’t know.”

On the other hand, here’s the same issue handled by someone who’s intellectually honest: the scientist, Laurence Krauss. He doesn’t have the same problem as the priest because he doesn’t have to tap-dance around demonstrably untrue theological claims. That means he can deal with things more directly, including the superfluity of gods in times of tragedy.

Why must it be a natural expectation that any such national tragedy will be accompanied by prayers, including from the president, to at least one version of the very God, who apparently in his infinite wisdom, decided to call 20 children between the age of 6 and 7 home by having them slaughtered by a deranged gunman in a school that one hopes should have been a place or nourishment, warmth and growth?

We are told the Lord works in mysterious ways but, for many people, to suggest there might be an intelligent deity who could rationally act in such a fashion and that that deity is worth praying to and thanking for “calling them home” seems beyond the pale.

…

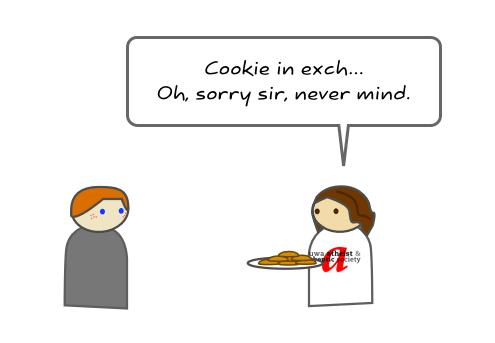

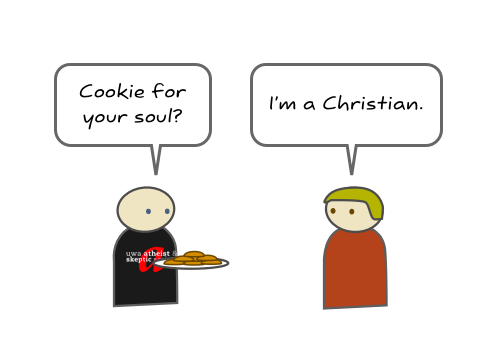

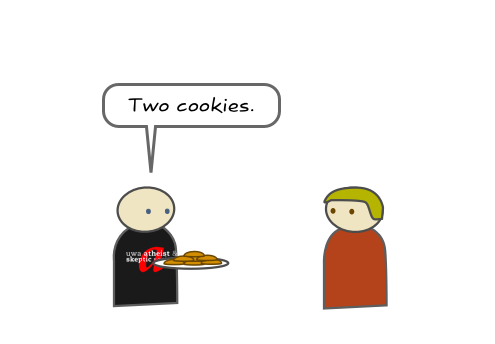

We don’t need faith to empathize with the grieving in Newtown. We can feel real connections, whether we are parents, or neighbors of families, or simply caring men and women. And we can want to help simply because of our common humanity.

Note that he identifies ‘common humanity’ at its origin: with humans. The difference in approach is striking. So is the relative capability of the authors. It helps if you’re not burdened by outmoded dogma and superstition.

Recent Comments