The big news in atheism this week: Alain de Botton wants to build an atheist temple. Which seems strange — atheism isn’t a religion, so why would it need to borrow religion’s trappings? I think de Botton tipped his hand, though, in this pronouncement:

The philosopher and writer Alain de Botton is proposing to build a 46-metre tower to celebrate a ”new atheism” as an antidote to what he describes as Richard Dawkins’s ”aggressive” and ”destructive” approach to non-belief.

Rather than attack religion, Mr de Botton said he wants to borrow the idea of awe-inspiring buildings that give people a better sense of perspective on life.

”Normally a temple is to Jesus, Mary or Buddha but you can build a temple to anything that’s positive and good,” he said. ”That could mean a temple to love, friendship, calm or perspective … Because of Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, atheism has become known as a destructive force.”

Destructive force? For me, Dawkins and Hitchens are two guys who have come to epitomise well-tempered reason, intelligence, and courage in the face of mortality, so de Botton’s criticism doesn’t ring true for me. I’d like to suggest a little test which I’ll call the S.E. Cupp test: When someone says they’re an atheist, do they spend more time promoting atheism, or castigating other atheists because of their tone? If the latter, then what’s the difference between them and a theist?

Dawkins has called the project a waste of funds, PZ says it’s a monument to hubris.

Me? I say it’s redundant. We already have a temple. I was there earlier this month. Or, at least, at one of them.

The atheist temple I went to was the Temple of Knowledge, and it’s better known as the New York Public Library.

It gots lions.

Why would I call it an atheist temple? Because it’s filled with the work of people. People; not gods. People (and you can see them there every day) engaged in the process of gathering knowledge and combining it to make new knowledge. This is the goal of science, which is an atheistic form of reasoning.

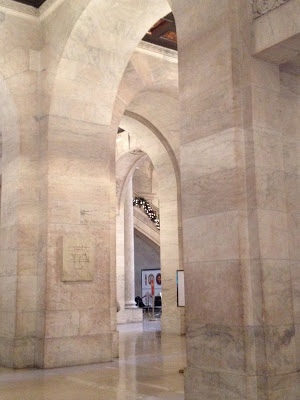

I walked along its halls of solid marble, where generations of humans have come to read and learn.

No gothic arches, these. How could you help but be in awe of not just the building, but the building’s purpose?

Like a temple, the magnificent Reading Room prompts a hush.

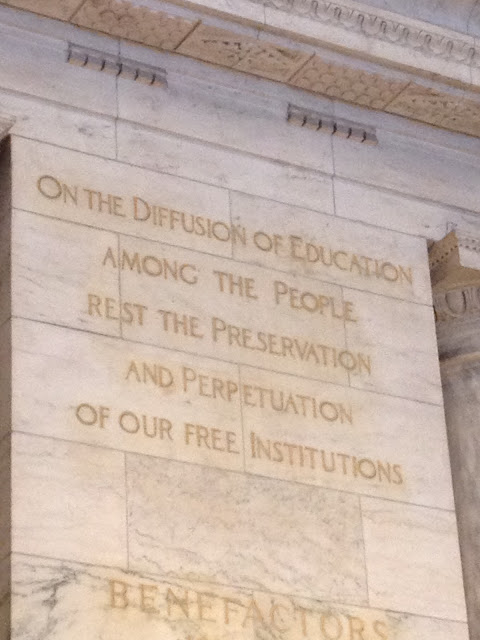

And the people who built this place — yeah, they were tycoons who made their money from the skins of small furry animals. But they wanted to build a place where the knowledge of the world could be preserved, and they cared enough to make it amazing. And they inscribed this on the walls, in letters big enough for anyone to read:

“On the diffusion of education

among the people

rest the preservation

and perpetuation

of our free institutions.”

I read that, and I think, you know, they got it. They really got it! Even back then. Our society depends on education. Our freedom depends on it. You can’t preserve freedom in a population of ignoramuses; they’ll just tear it down again the instant they feel afraid. It’s such an alien concept in this age, when one political party has dedicated itself to the destruction of the Department of Education, and (through homeschooling) constantly works to undermine the public school system so that children will be protected from education. It seems like a quaint and noble sentiment, but we need to relearn this thinking that came from better minds than ours. Just as we need another quaint and antiquated notion symbolised by libraries: the public good.

But that’s not all I saw. There were treasures.

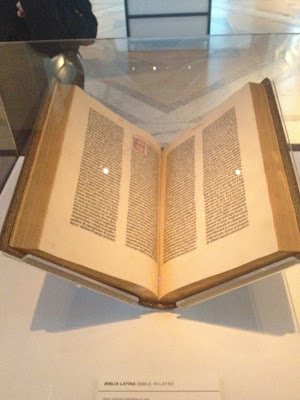

Holy shit! It’s a Gutenburg Fucking Bible! One of only 40 perfect ones left. Yes, it’s a bible because for some reason, people thought the Bible was important back then. But what this book did was make reading and publishing commonplace. That’s much more important than the book’s rather poor contents.

And check this out: it’s Christopher Robin’s toys! That’s not just Winnie a Pooh — it’s Winnie THE Pooh. And the others! It was great to see them there, even though it made me think of Toy Story 2. I look at Tigger and realise that Ernest Shepard really nailed it.

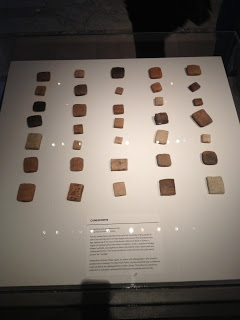

These are clay tokens with cuneiform on them, some of the earliest writing that people ever used. That made it possible for people to transmit knowledge over generations.

And while I was in this Library, I felt so connected to people in other ages and to the future. It was a feeling that I can only describe as spiritual, even though I don’t like that word. But it was the same feeling that I felt in the old religion but more intense and meaningful.

You can keep your paltry theist cathedrals. Do not copy Mormon temples — they are monuments to superstition and foolishness. Let St Patrick’s fall. Instead, build a library, Mr de Botton, or an observatory, or a university, or a museum. They’re the only temples that atheists have any business building.

Actually, St. Patrick’s will make a very nice reading room in about 100 years.

Recent Comments