Some linguists are saying that the documentation of every human language should be complete by 2015. That’s good, right?

Erm…

Protestant translators expect to have the Bible — or at least some of it — written in every one of the world’s 6,909 spoken languages.

“We’re in the greatest period of acceleration in 20 centuries of Bible translation,” said Morrison resident Paul Edwards, who heads up Wycliffe Bible Translators’ $1 billion Last Languages Campaign.

A lot of work in linguistics has historically been done by Protestant missionaries, including the Wycliffe Bible Translators and SIL International. They take their cue from the scriptural injunction to preach Christianity to all nations.

I’m actually glad that they’re documenting languages. Or rather, they’re translating the Bible into various languages, and hopefully documenting more about the language along the way. It needs to be done. I don’t even mind that their translation efforts are focused on the Bible. It’s a good basic text, a little archaic, but not bad for expressing a good number of concepts. And as a bonus, the Bible has already been translated in many languages, and the texts are already aligned by chapter and verse. It’s like the ultimate cross-lingual parallel corpus! Potentially good for machine translation.

What concerns me about these efforts is that they come into it with what amounts to a Christian agenda. Despite protestations to the contrary.

“Wycliffe missionaries don’t evangelize, teach theology, hold Bible study or start churches. They give (preliterate people) a written language,” Edwards said. “They teach them to read and write in their mother tongue.”

The missionaries develop alphabets. They create reading primers. They translate the Bible.

Distributing bibles is evangelising. The difference between making bibles and more overt conversion efforts is a thin line. (Although in one case, the conversion backfired.)

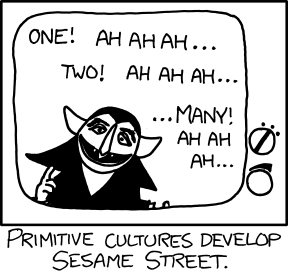

What’s more, this Bible-driven approach to language documentation misses a key point of language. A language — its vocabulary, kinship terms, lexical categories, and even speech acts — encodes some social ideas that are incomprehensible from outside the system. Coming in to promote a Christian worldview can only hamper the understanding of the language.

Watch the line between linguist and missionary vanish as this volunteer waxes rhapsodic about the effort.

“I am excited to put God’s word in all people’s heart language,” Zartman said. “Until people can read the Bible in their own language, God is a foreign concept.”

You mean the Christian god is a foreign concept. And it ought to stay that way. Help them by documenting their language, but leave the imported religion at home.

Recent Comments