Here’s an old mission companion, on a thread about this:

Mormon Church to exclude children of same-sex couples from getting blessed and baptized until they are 18

Children living in a same-sex household may not be blessed as babies or baptized until they are 18, the Mormon Church declared in a new policy. Once they reach 18, children may disavow the practice of same-sex cohabitation or marriage and stop living within the household and request to join the church.

The policy changes, which also state that those in a same-sex marriage are to be considered apostates, set off confusion and turmoil among many Mormons after the policy was leaked online. The changes in the handbook for local church leaders for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were confirmed Thursday by church spokesman Eric Hawkins.

My former companion says:

>I received a witness of he Church as a young 19 year old as I pounded the streets of Perth with many of you.

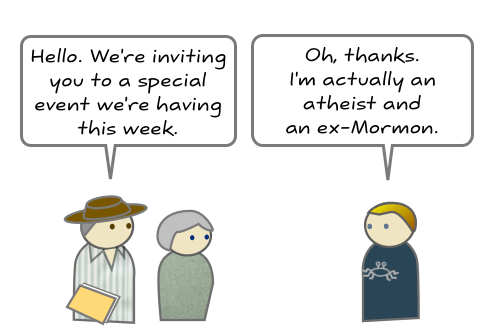

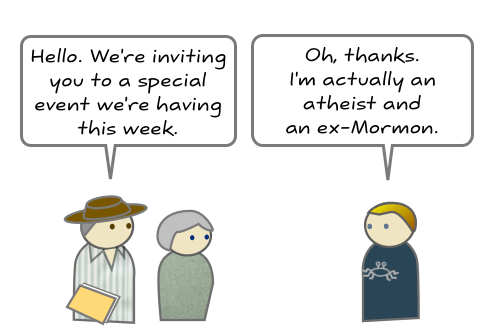

Thank goodness when we knocked on doors, we didn’t have to say, “Hi! We’re missionaries from the Church of… er… your parents aren’t gay, are they? Good, we’ll continue.”

I’m wondering how missionaries today will keep from inadvertently teaching someone who isn’t eligible.

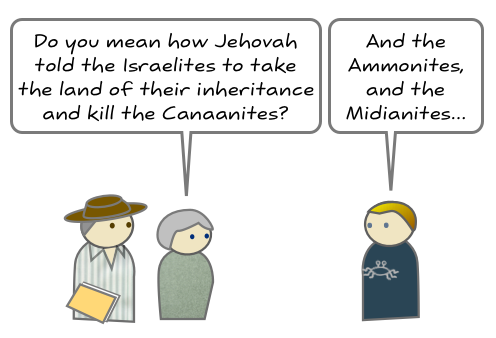

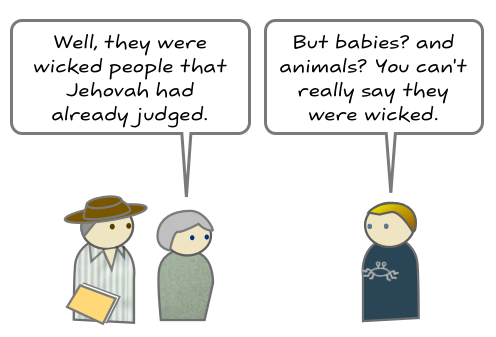

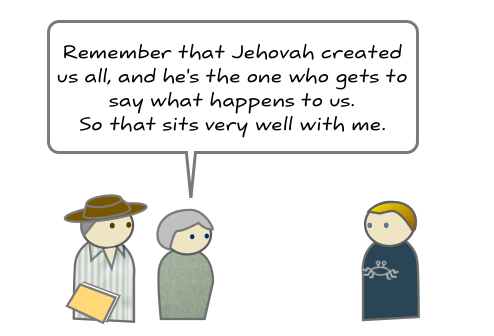

>I believe in God and I believe the LDS church is his church. If this is what God has decided then it’s not for me to argue.

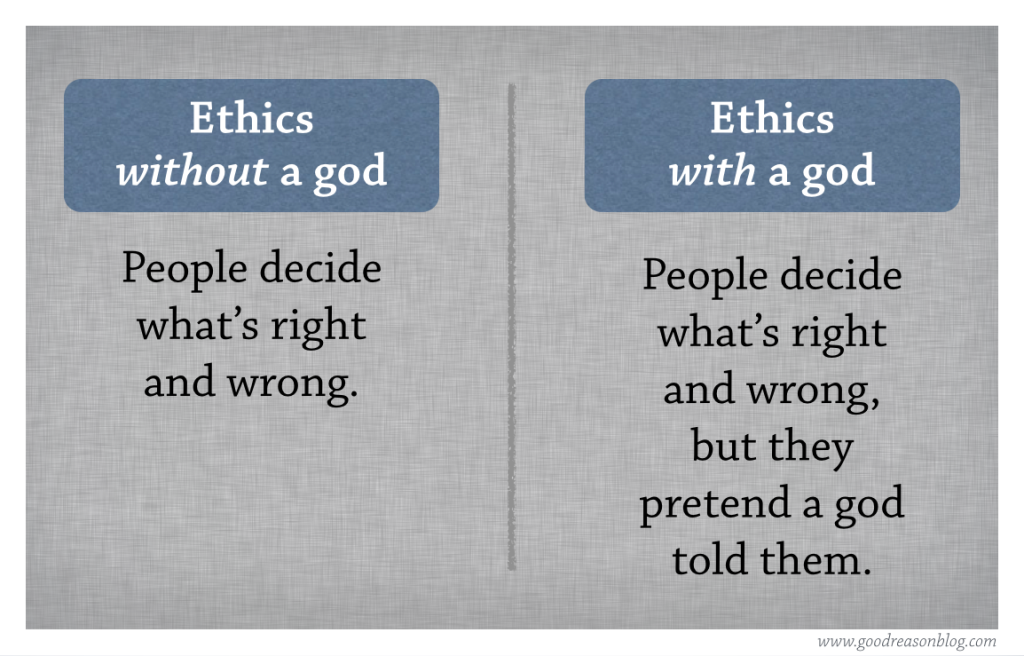

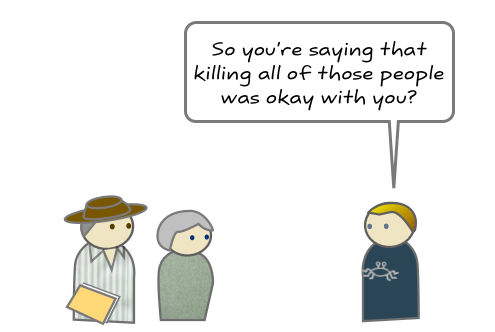

I would say that this cruel and unfair policy is convincing evidence that either

- LDS leaders are operating from a source other than a just and fair god — be it their own prejudices, or their own principles, or

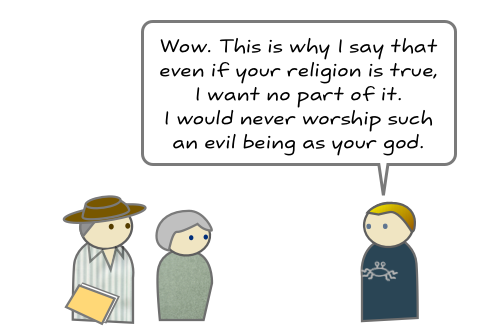

- the god that Mormons worship has an inordinate concern with the sexual behaviour of humans, but is unconcerned with justice. And, in my view, is not worth worshipping.

Or perhaps both.

>Maybe I’m too simple in my views but what I fought for as a 19 year old when I laboured with you all then has not changed now.

Our views should change as we get older. As Paul said, “When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child. But when I became a man, I put away childish things.” I think homophobia is a childish thing, and worse, it harms people. In my life, I’ve made gay, lesbian, bi, and trans friends, and some co-workers. I’ve learned that there was a commonality to our life experiences, and that any prejudice I might have felt toward them was my own problem. And I’ve sorted it out. I’ve learned that every member of a society has the right to equal treatment.

Sadly, the LDS Church hasn’t learned this — speaking of the church collectively and not individually, of course. It has formed harmful and cruel policies, and now it has doubled down on them. Well, as an exMo, it would be easy to say, “What do I care — I’m no longer in the church.” But the climate of homophobia fostered by the LDS Church is having a harmful effect on LGBT people, especially the ones in the church. It is setting children against parents — a potential convert will have to leave the supportive environment offered by gay parents, turn their backs on them and denounce their relationships. Wow. That’s cold.

Kids (even straight kids) in blended families won’t be able to participate in the church they’ve grown up in, because one set of parents is in a gay relationship. Suddenly ineligible. And this is contrary to AoF2; the kids will be responsible for the actions of their parents.

Does all of this seem right to you?

Fortunately, most people in “the world” are starting to operate from a position of kindness. They are showing more compassion and love than the LDS leadership is currently capable of.

You may be too far into the LDS community to see how regular people regard this. When I tell my neverMo friends about this, or who they see it in the news — yes, it is hitting the news — they’re horrified. And it confirms to them that the church is a homophobic organisation. It is — as we call other groups when they exist to promote bigotry — a hate group.

The leadership will eventually change on this issue, just like they did with race and the priesthood. They’ll walk it back with an anonymous essay on the website, if we still have websites then. Until then, they (and you) are on the wrong side of history. They’ve chosen exclusion and bigotry.

What will you choose? Understanding and compassion? Or obedience?

Recent Comments