Only a couple of years ago, I would have been horrified if my kids hadn’t wanted to be active in the Church. Now, after my deconversion, I’ll be horrified if they do. I realise it’s a major flip, and it must be confusing for the little dears. Their mother is still taking them to church, and as I watch them go every Sunday, I feel a sense of dread. I think it’s the same feeling as the mom from that scene in Erin Brockovich. You know the one:

INT. IRVING HOUSE, LIVING ROOM – DAY

Another copy of those DOCUMENTS, now in Donna’s hands. She’s

on her couch with Erin, reading them. Outside, Donna’s two

daughters are playing in the pool. She reads the last page

and looks up at Erin, bewildered.

DONNA

An on-site monitoring well? That means —

ERIN

It was right up on the PG&E property over

there.

DONNA

And you say this stuff, this hexavalent

chromium — it’s poisonous?

ERIN

Yeah.

DONNA

Well — then it’s gotta be a different than

what’s in our water, cause ours is okay.

The guys from PG&E told me. They sat right

in the kitchen and said it was fine.

ERIN

I know. But the toxicologist I been talking

to? He gave me a list of problems that can

come from hexavalent chromium exposure. And

everything you all have is on that list.

Donna resists this idea hard.

DONNA

No. Hunh-uh, see, that’s not what the

doctor said. He said one’s got absolutely

nothing to do with the other.

ERIN

Right, but — didn’t you say he was paid by

PG&E?

Donna sits quietly, trying to make sense of this. The only

sound is the LAUGHING and SPLASHING from the pool out back.

Then, gradually, Donna realizes what it is she’s hearing —

her kids playing in toxic water. She jumps up …

DONNA

ASHLEY! SHANNA!

… and runs out to the pool. Erin follows her.

EXT. DONNA’S HOUSE – DAY

From the door, Erin watches Donna run to the edge of the pool

in a frantic response to this news.

DONNA

OUT OF THE POOL! BOTH OF YOU, OUT OF THE

POOL, RIGHT NOW!

SHANNA

How come?

DONNA

CAUSE I SAID SO, THAT’S WHY, NOW GET OUT!

OUT! NOW!!!

Erin watches compassionately as Donna flails to get her kids

out of the contaminated water.

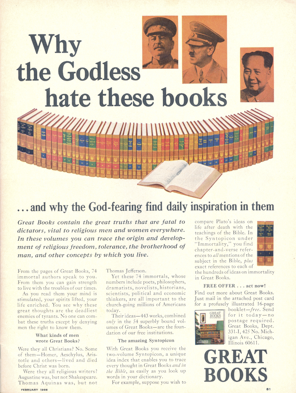

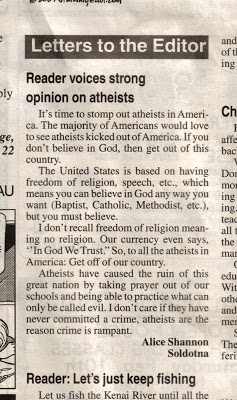

Now surely that’s too dramatic, isn’t it? Swimming in a toxic pool isn’t the same as going to church. What harm is religion going to do them? The harm is this: religion kills critical thinking skills in people who are most devoted to it.

Religion offers a substitute for reason. It offers faith instead of evidence. Instead of teaching that something’s true because it’s well-supported, it teaches that something’s true because

a) the holy book said,

b) the man at the pulpit said, or

c) it ‘feels right’.

Psychological traps such as wishful thinking, anecdotal evidence, communal reinforcement, selective sampling, and confirmation bias are part and parcel of the religious experience. Their use is encouraged and rewarded by the group. With all these fallacies in play, religious devotion is going to hamper good reasoning and encourage fallacious thinking. And this will cause bad decisions along the way. What parent wants to see their children make bad decisions? Or what parent wants to hinder their child’s thinking skills? Yet this is what religion does.

So even though all the ‘golden rule’ talk is pretty innocuous, I sometimes want to grab my boys out of Sunday School, tuck one of them under each arm, and run out of the building to make the brain damage stop.

What can the deconverted parent do to help children reason despite the influence of religion? While it’s difficult for me not to be negative about religion (as you’ve noticed), on better days I use a more positive approach:

Teach reason. Learning how to examine ideas is a skill children will use throughout their lives. And it’s less controversial to believing family members than bagging religion to the kids. When Youngest Boy asks, “Do you think the Golden Plates are real?”, I like to ask “How could we find out?” I get them to think about what sort of evidence would be adequate, and what sources would be reliable. Sometimes I show them optical illusions, and I tell them about crop circles and Bigfoot, and how easy it is for people to be fooled.

It’s usually in the car that we talk about logic and fallacies. Yesterday in the car, the boys were arguing about something, and Oldest Boy said, “You made the claim, so it’s up to you to provide the evidence!” Once I blew on the lights to ‘change’ them, and when I said, “Look, it worked,” Youngest Boy said, “That’s post hoc, Dad.” And I thought, I must be doing something right.

I suppose I should add that I like teaching reasoning skills rather than teaching that Religion Is Bad because, you know, I could be wrong. They’ll need to work that one out themselves.

Teach religion. Under most circumstances, I’d fight hard to keep religion out of schools. But my kids’ school teaches a lot of religion, and I couldn’t be happier. Why? Because they teach everything from Norse myths to Hinduism. They go through Greek and Roman mythology, the lives of Catholic saints, and Australian Aboriginal creation legends. By presenting Christian fables as one set of stories among many, it naturally raises the question: what claim does this religion have as the ‘true one’ when so many other people have believed so many things? Why does Mom believe in Jesus and not Zeus?

There’s an added benefit to telling my kids religious stories: it inoculates them. Parents who raise their children without religious instruction run the risk of them contracting it in a world of infected people. I’ve seen a number of cases where parents do a great job of raising kids secular, but then later in life someone gives them a copy of ‘Mere Christianity’ and they think it’s the greatest thing they’ve ever seen. If they’d been taught about Christian mythology (and Greek, and Norse, etc), they’d realise they’d heard it before, and we wouldn’t get them in church saying “My family doesn’t know about the Gospel.”

So I don’t mind so much when the boys go off to church with their mother. I just wave and say “Bye kids! Remember to ask for evidence!”

I don’t envy their Sunday School teacher.

Recent Comments