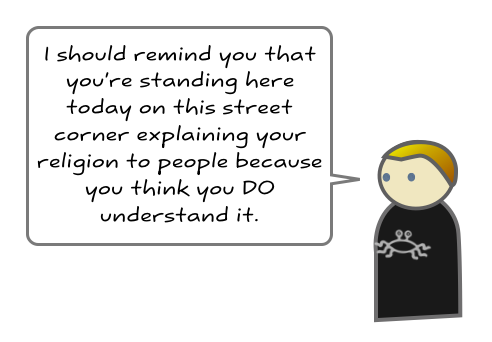

I’m sure I’ve mentioned before: I always engage with street evangelists. If they’re putting their ideas out there in public, those ideas are fair game for discussion and ruthless examination.

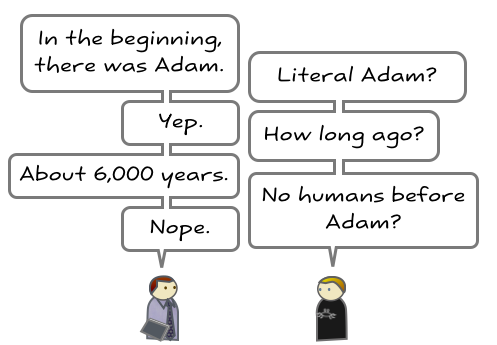

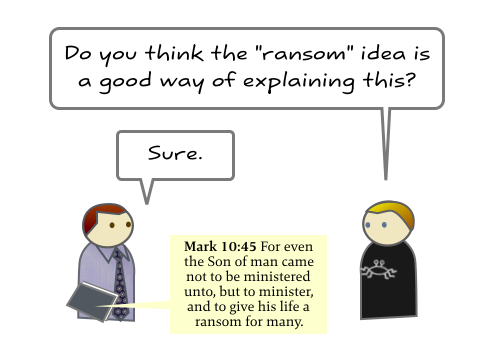

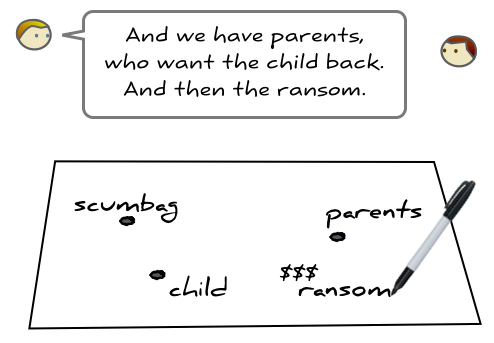

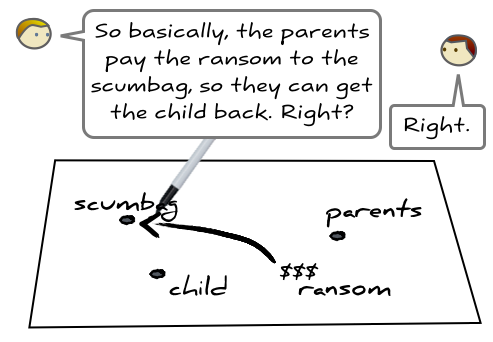

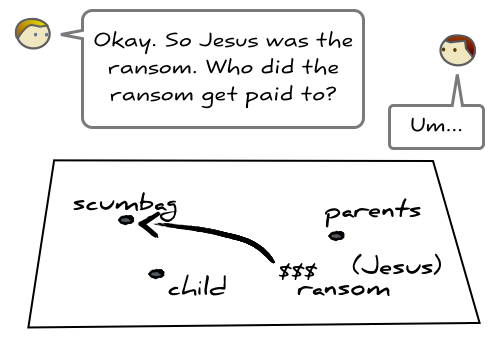

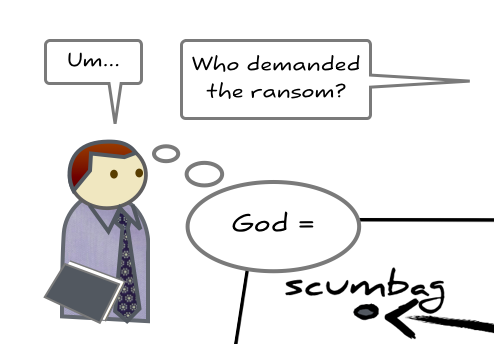

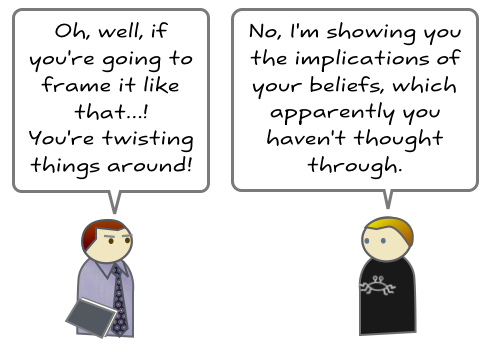

Here’s a discussion I had with a Witness of Jehovah. It went pretty much exactly like this. Feel free to use and adapt.

There are loads of problems here. Human evolution and human civilisation go back way farther than 6,000 years. But it’s a mistake to get bogged down here. Keep it moving.

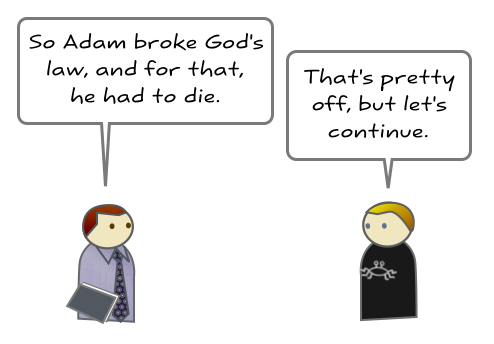

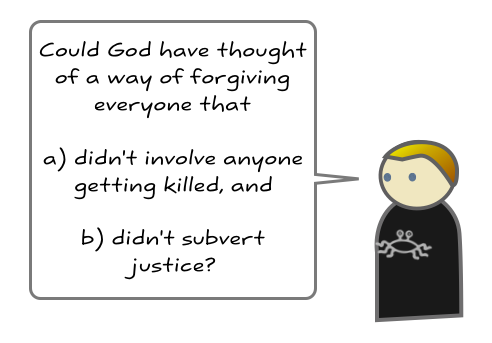

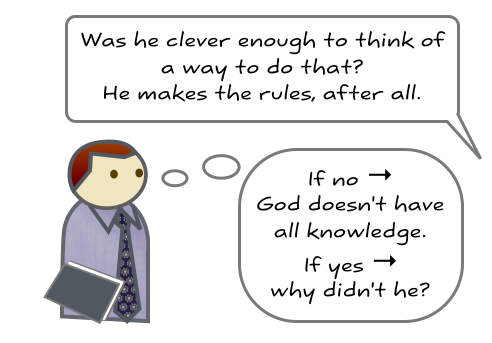

Sin is a problem of God’s own making. He decided that he couldn’t stand some things. Then, having created the problem of sin, he decided to blame humans for the problem that he created.

Another problem: Jesus came back to life. You don’t get the ransom back! How is that a sacrifice?

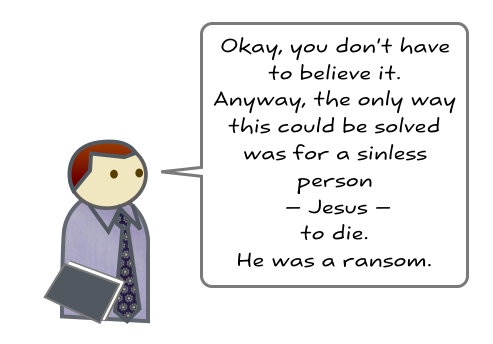

Yet another problem: If God wanted a sacrifice, then he got one; he should be satisfied, and the process should be over. But it’s not; God expects us to believe in him. When someone pays a ransom, the kidnapper doesn’t then require the parents to ‘believe’ in him.

This is problem of its own; isn’t justice simply what God says is just? in which case he could do anything, and then declare his actions just by fiat. On the other hand, if there’s some external principle of justice that even God has to obey, then he must be subordinate to some principle. Then why worship God at all? Why not skip the middleman, and worship the principle instead, since it’s higher than God is?

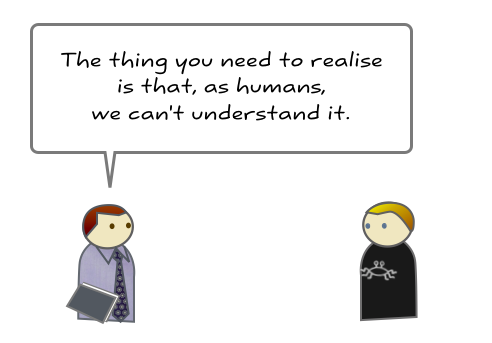

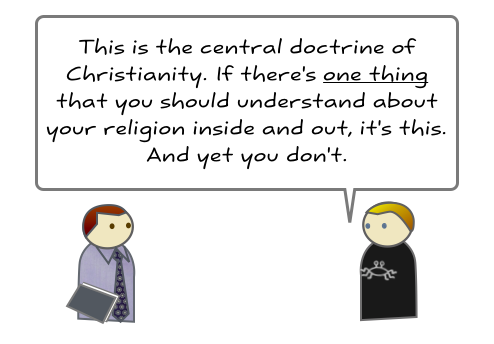

This is a dodge to terminate the thought process. You could say any wild thing, and then refuse to defend it on the grounds that humans can’t understand it.

And again, why did God decide to make a solution that makes no sense? If humans need to believe this to be saved, then it needs to make sense to humans.

I think we can understand it. God is a bloodthirsty maniac whose ultimate idea of compassion is a human sacrifice. And he’s that way because he was imagined up by bloodthirsty people. That’s not hard to understand.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Thanks for stopping by! If you like this cartoon, I got more.

21 December 2015 at 5:46 am

BRILLIANT! Thank you!

21 December 2015 at 3:21 pm

Excellent! And isn't their heaven full?

21 December 2015 at 5:51 pm

Loved / linked it.

Hope you don't mind…

Postback URL: http://www.stupidatheist.com/2015/12/21/godisascumbag/

22 December 2015 at 12:53 pm

Actually if Jesus is god then the kidnapping was faked.

22 December 2015 at 1:02 pm

Wouldn't god be the parents in this situation? Jesus the child and the ransom being Jesus's life? We the humans as the evil scumbag (who are demanding forgiveness?)

22 December 2015 at 2:24 pm

It's an interesting point, but I don't know if that's true. Does the biblical story tell of people asking for forgiveness before Jesus was born?

I know that the lord's prayer mentions forgiveness, but that is not specifically of sins, rather of trespasses, which might or might not include sins.

Up until Christianity, I thought that sin was just something you had to deal with yourself (albeit through rituals), so asking god to forgive it wouldn't make much sense.

22 December 2015 at 2:31 pm

Nope. Who goes gets killed (goes to hell) if the ransom isn't paid – the parents or the child? Who arranged this whole thing to go down – the all-powerful, all-knowing all-powerful being or the finite, limited being? Who is being judged by whose standards? Who is receiving the "ransom." Xtian theology is an incoherent mess.

24 December 2015 at 6:18 pm

Interesting scenario, but it wouldn't explain it either. I see the parents as the current human condition before the crucifixion. I see the child as the future human condition. Jesus and his death is the ransom (payment/sacrifice). So the ransom is paid to give the child or children a new future. But who set up the rules and the whole situation? The kidnapper or scumbag. It only leaves God to take that position. Also, the sacrifice wasn't even a sacrifice, it is then a scam since the death was not a real "death", just a bad weekend. No ransom was actually paid.

24 December 2015 at 11:32 pm

>Does the biblical story tell of people asking for forgiveness before Jesus was born?

There's Jonah. The people of Ninevah asked for forgiveness, and they got it. No sacrifice required. So this Jesus thing is a bit of a scam.

22 December 2015 at 1:19 pm

Theologically Christ is the ransom, per the verse quoted (and others). We voluntarily sold ourselves into slavery to Satan through Adam's sin. We are the child. God is the parent. Christ is the ransom, paid to the scumbag that owned us (Satan). The scumbag that demanded the ransom was Satan, so God sent Jesus to pay it. Also, when making the argument Jesus=God, it makes it that much more of a ransom. He gave his own life as the parent, became the ransom to sell to the scumbag to set us (the children) free.

22 December 2015 at 1:28 pm

"We voluntarily sold ourselves into slavery to Satan through Adam's sin."

I didn't volunteer for anything and I'm only responsible for my own actions, not Adams.

Please explain how God wasn't the one demanding the ransom and how we have been set free? What were we freed from?

22 December 2015 at 1:45 pm

Yeah, there's that dual-God Christianity again. Look, Satan is not an entity equal with God. God created Satan and knew all his works from the very beginning. Could God have arranged creation so that there was no Satan? If so, why didn't he?

22 December 2015 at 4:40 pm

Wow, when you put it that way, it sounds even stupider than when a priest tried to explain it to me.

23 December 2015 at 3:28 am

What Speedwell said above; plus God invented the concept of "sin" – the breaking of his "law". All of these things are sociopathic behaviours unworthy of an omniscient and omnipotent being. They simply reflect the desire of Hebrew religious leaders to impose their wills on the rest of their people, hence their invention of God, his laws, sin, atonement (payment of money to the priests to intercede etc.)

25 December 2015 at 12:32 am

But who set up this whole system? And in your scenario, it seems that Satan is at least as powerful, if not more powerful than God. Why would God wait so long to finally pay the ransom anyway? And why didn't he just destroy Satan and be done with it? His first attempt was the supposed great flood after he was fed up with sin. Sounds like God's "plans" are not well thought out.

22 December 2015 at 2:03 pm

"We voluntarily sold ourselves into slavery to Satan through Adam's sin."

Why should Adams actions be crucial for my life?

It is like saying:

The father have killed someone, but the father and all that come from his seed are going to be jailed for eternety,even the unborn!!

Really, you call that justice?

But wait, it was not even a murder, but a bite from an apple, from people who did not know what is right and wrong?

That certainly deserves eternal punishment, right?

"The scumbag that demanded the ransom was Satan"

When and where does it says that he did that?

And God is powerless against his creation,

therefore he had to give his life to Satan, really?

"He gave his own life as the parent"

If he gave his life for us, is he dead now?

That would explain why he is silent and nowhere to be found, right?

22 December 2015 at 2:40 pm

I can't speak for contemporary Christianity, but medieval theologians framed the transmission of original sin as a sort of biological process, and often preferred the language of Romans (Christ as physician) over that of Mark. It's also interesting to note that the canon of Christian mythology points to angels as the first to introduce sin into the world, which God allowed in order for it to function as a point of reference to further glorify his creation. Most Christians are unaware of these types of nuances, and are perfectly willing to write off ancient/medieval/early modern Christianity as archaic. That seems all sorts of problematic to me.

Anyone interested in sin as a biological process should consult primary sources. Peter Lombard's "The Sentences," Saint Augustine, Hildegard Von Bingen's "Holistic Healing," Thomas Aquinas, Hugh of Saint Victor.

Interesting stuff, though it would go right over the heads of your typical street evangelists. Really illuminates the discordant, fractious, inconsistent mess that is Christianity.

22 December 2015 at 3:51 pm

Damn Midichlorians.

23 December 2015 at 8:07 am

I find it humorous that there are so many 'believers' who feel it necessary to defend their 'god' on posts like these. Would an 'omnipotent' being really need YOU to defend him?

25 December 2015 at 6:51 am

Well, to be fair, they're not defending God, their defending their views about God. Obviously different, I think.

24 December 2015 at 2:19 am

What I don't get is that if he was sacrificed to forgive original sin then shouldn't everyone since have been born free from sin. But since he came back, I guess the "sacrifice" was a meaningless gesture.

25 December 2015 at 4:45 am

I think the problem here is that the JW doctrine of the atonement is not the only doctrine of the atonement (hence a refutation of the JW doctrine cannot be said to render all Christian atonement doctrines incoherent). I am also not sure that the JW apologist portrayed in this post even explained the JW doctrine correctly.

I have two issues with this particular response to Christian atonement. The first is that the ransom analogy does not capture the wholeness of salvation history, as seen most obviously in the standard Christian understanding of the Resurrection, not the Death of Christ, as an essential component of atonement. Also, atonement is not something that just "happens" when Christ dies; rather, it is quite apparent from Jesus's moral teaching and interactions with his followers that there is an existential demand that is placed on the Christian, who must live out Christ's moral and religious example. Christians are saved by the grace of God, but the conferring of this grace involves a lifelong process of sanctification in which the Christian lives out a moral life. While God ultimately saves, Christians must also life out their lives in the person of Christ for atonement to "happen."

Second, I take issue with the kind of Euthyphro objection leveled here: if something is good (or in this case just) because God wills it to be so, then goodness is arbitrary (I don't see why this should follow, as I explain below); if God wills something because it is good, then God is subordinate to a higher principle of good. This however, mistakenly creates a divide between God, as an omnibenevolent being, and an Ultimate principle of good (what grounds this ultimate principle of the good if not an ultimately good being?). Rather, there is NO distinction between an ultimate principle of the good and an ultimately good being, because an ultimately good being contains the ultimate principle of the good. In other words, what an ultimately good being wills is ultimately good precisely because and ultimately good being wills it. How else would one ground an ultimate principle of the good? It cannot be grounded merely in the universe, since the universe is contingent (it could exist otherwise, or not at all) and as such cannot be grounds for any ultimate principle.

25 December 2015 at 2:42 pm

That just means that if god were to decree that infanticide is moral, then it is.

So morality would be arbitrary.

Your argument seems to be that it can not be anything other than arbitrary, because that's just the way god and morality work.

Do I understand you correctly?

27 December 2015 at 10:40 am

No, it doesn't seem that you do understand me correctly. A morally perfect being would by definition not decree something immoral as moral. How WE as humans understand perfect morality is its own question, but you make a mistake in presupposing an ultimate moral value (infanticide is wrong always and everywhere) and assuming that a perfectly moral being would not impose an ultimate moral value. Now, if you want to talk about ultimate/objective morality sans God, it's going to get a pick tricky to ground such absolutes.

27 December 2015 at 4:53 pm

If a morally perfect being would not decree something immoral as moral, then why is that?

Is it because the being decides what is moral (in which case morality would be arbitrary), or because there is a standard by which the being decides what is moral (in which case god is not the source)?

Any which way you turn it, the Euthyphro problem stands.

Luckily, an absolute morality is not necessary at all, because we have a shared morality. That shared morality changes over time (the most obvious example is the change regarding slavery in western society), but that doesn't invalidate it as a moral standard.

27 December 2015 at 7:20 pm

Bram, you're not getting my point, man. You're arbitrary creating a division between an ultimate moral principle and an ultimate moral being. Why should we suppose such a division exists? If there is an ultimate moral principle, it is not contingent and hence grounded in a necessary being. The only source to which that being refers when imposing moral values on a created word is that being itself. There is no separation. How we come to understand that moral principle is through reason AND revelation. That moral principle is itself rational, otherwise it would be useless to rational beings. Because it is rational, it is not contradictory or incoherent. Any ultimate moral principle expressed through an ultimate moral being for rational agents would therefore NOT impose moral values which the rational beings find to be obviously contradictory or, indeed, immoral. This is just standard moral theology here.

As for this adaptive shared morality bit, the one thing you have to countenance there is cultural relativism, plus the fact that there are clear disputes in what is moral, which both challenge the notion of even a contemporary let alone enduring shared morality. In effect, there does not seem to be a shared morality that emerges from society alone. That morality, as we see in cultural and indeed intercultural moral disagreements, quite simply does not obtain.

27 December 2015 at 7:54 pm

But if there is no separation, then good is whatever god is, right?

In that case, it is arbitrary, again.

As for a shared morality:

Yes, there is no universal shared morality, but that wasn't what I was talking about anyway. I was talking about shared morality in a more general sense. It differs between cultures, but also between political parties.

However, there are enough points of convergence in any given society to build a framework from.

Also, there does not seem to be any indication that morality cam from anywhere other than humans.

The morality in the bible (even the new testament) is outdated compared to current morality, so that's not where we get our current morality from.

If we are imbued with it by god, then it's not detectable, specifically because of what you said:

"…That morality, as we see in cultural and indeed intercultural moral disagreements, quite simply does not obtain."

If anything, cultural evolution is a much better explanation of the current moral landscape than divine command is.

27 December 2015 at 8:49 pm

Bram, what exactly do you mean by arbitrary morality? That it could be otherwise? That it is simply the product of a will? If you look back at my last post, you will see that the moral theology I am forwarding here is rationalist, hence, it is not "simply the product of will" though it has to do with a will. Also, because such morality is associated with a necessary being, it could not be otherwise. So I'm not quite sure how you are deciding that such a morality is arbitrary. I think the main hold-up here is the notion that God is necessary being. It is true in a sense that this moral theology would suppose that God IS the Good/moral, but God is not ONLY the Good/moral; rather, that is just part of God's definition.

Second, it seems I should have been more clear. When I say that morality cannot be grounded ONLY in society, I do not mean that humans have not come to understand and enact moral precepts through society. Rather, what I mean is that something is not morally correct simply because one society declares that something is moral. At root, an understanding of morality is rationalistic (and as I will note later, a grounding of morality is theological). However, even by way of reason, disagreements over morality emerge. This is why I mentioned reason AND revelation as means of human understanding of morality. Now, when it comes to grounding morality, that is done theologically, or, at the very least, metaphysically. That is, morality is understood with reference to normative precepts that are not simply based on the fads of the time, but are, at base, enduring, even if their manifestation and application changes through time.

You speak of moral development and cultural evolution. Moral development is certainly possibly, but if moral development is anything but arbitrary (not based in reason and not grounded) then it must proceed toward some telos or standard, right?

This is the problem with relativistic moral development. If there is no necessary end or telos, how is moral development possible? Could we not simply backslide toward "degenerate" morality? How do we decide what "degenerate" morality even is? Is it just what is older? What if we're developing in the wrong direction? The main problem I'm seeing here is that you seem to just think that newer morality is better. But what is that based in other than temporal whims?

27 December 2015 at 9:26 pm

But earlier I already asked you whether the arbitrariness of morality under divine command theory was by design. You seem to be confirming this.

You ask me why an arbitrary morality is bad?

Because if it is, then we can't simply build a model/framework to build upon as time goes by. It would mean that we would have to treat every moral question as a separate thing, and we can't infer from prior knowledge whether it is or isn't moral.

We would have to treat attempted murder as different category than first degree murder, not as a less severe version of murder, because if morality is arbitrary, one of the two might be moral.

And that is all just to say that, even if we don't have a naturalistic explanation for morality, that still wouldn't validate divine command theory.

28 December 2015 at 3:17 am

Bram, would you please re-read my last post? I am, first off, NOT forwarding a divine command theory. I am simply pointing out that God wills the Good because God is an ultimately moral being who contains the principle of the ultimate good. Divine command theory says that something is moral because God commands it; I, however, am describing how God grounds ultimate goods as an ultimately moral being, which stipulates that there is no divide between the ultimate moral principle and and God as a necessary and ultimately moral being. Two very different concepts of morality.

Second, I asked you what you meant by an arbitrary morality. I still don't know what you mean by that.

I'd like to hear more of what you think on the lack of telos / guiding principle in a relativistic morality AND how we determine what moral progress is.

As far as developmental, non-arbitrary, and non-relativistic morality, the whole idea is that moral foundations do not change BUT we have to further our understanding of them and apply them to new situations. Developmental morality does not entail relativistic morality. Far from that, it entails a fixed moral goal toward which we progress.

28 December 2015 at 10:29 am

But what is it that makes god an ultimate moral being?

If it only because he's god,then "moral" loses its meaning, because god would be moral despite doing things which we now consider to be immoral (which is why I said that your description would yield an arbitrary morality).

And if god can't do things that are considered immoral, then he's limited in his will, which means he's not omnipotent, which seems like a deal killer for an ultimate being.

28 December 2015 at 7:07 pm

I'm really starting to think that you're not actually reading my posts, which doesn't make for a very productive conversation. Cf. above where I talk about the "rationalistic" character of God and the non-arbitrary nature of morality for rational beings. The whole point there is that an ultimately moral being imposing a moral code on rational beings (i.e., humans) would impose a moral code that is intelligible to them. Hence, God would not impose a morality that would go against our best moral reasoning, so God would not declare that which we would find to be contradictory or obviously "immoral" as moral.

Likewise, God's omnipotence is not transgressed if God does not will what is immoral, because it would be a logical contradiction (that is, a "non-act") for an ultimately moral being to will something immoral. An omnipotent being's omnipotence is not challenged by "non-acts," i.e., the whole "stone too big for God to lift" deal. God doesn't go against God's own nature. I'm just trying to give you a line-of-sight into reasonable theology here.

28 December 2015 at 7:42 pm

Here is a summary of what I think your position is. Please clarify where I misunderstand you:

God will only give the beings he created the morality which fits them.

Right so far?

But that means he created us in such a way that we would think murder is wrong, so that we would accept the morality he gave us, in which murder is wrong.

But then there is no more grounding of morality beyond "murder is bad" is part of god's nature.

I have heard it said by some theists that there needs to be some grounding somewhere for morality, and that god is that grounding, but in that case, the consequences of our actions aren't important in judging what is bad or good, because those are reasons beyond god for why something is good or bad.

You try to sidestep this by saying that good and god are one, but then what is "good", if you can not describe it on its own?

Someone is a good person because they have donated to charity. Charity is good because it helps people. Helping people is good because it makes people feel good.

If something is good because it has the properties of god, then how can we say that god is good? You'd essentially say that god resembles god.

You shrug off the "stone too big for god to lift" question as if it were nothing, but really, it illustrates that omnipotence is a paradoxical property. It can not exist.

And before you tell me that god is not bound by logic, I'd have to ask you to demonstrate that with more than arguments. Actual evidence is in order.

29 December 2015 at 8:50 am

Bram, thank you for introducing some more interesting points into this conversation. Indeed, understanding what the "good" is, is very important. Goodness is not merely an imposition, but also depends upon outcomes. However, if we look at instance involving moral luck, we will realize that outcomes cannot be the only determinant factor for moral actions (e.g., a man tries to kill another man by throwing a stone at him but actually strikes him in a such a way that he alleviates the man's back problem, thereby causing him to feel better; clearly this is not a moral act, as its intent is malicious).

Morality is complex, as it describes how we should act based on outcomes, intentions, tradition, and, ultimately, upon moral values. The reason why God, as an ultimate moral being containing the ultimate moral principle, is so important for morality is because God grounds these normative values; that is, the reason why we can say that murder is wrong everywhere all the time is not only because murder has certain consequences (indeed, we can conceive of cases in which murder is painless and the death of the murdered individual is desired by the individual, but that does not render that instance of murder moral). Nor, indeed, is murder wrong only due to the intentions of the murderer, as we can conceive of societies and situations that approves of violent acts in which pain is the desired outcome. Rather, to make normative claims, we require some kind of absolute, which is found in a necessary being. Attempts to ground such absolutes outside of a necessary being or necessary moral principle fail because they base themselves in contingent matters such as human societies or individual perceptions of pain, which run up against problems such as the fact/value distinction, as well as issues of relativism, to which I have alluded above.

Realize that the theology I am forwarding here (which is similar to the theology forwarded by thinkers as far back as St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas) is a rationalistic theology. God's nature is intelligible to human reason, though not contained by it. Goodness is indeed something we can figure out through reason — it is far from arbitrary — but the only way to ground it absolutely is through relation to an ultimate moral principle contained by an ultimate moral being. Again, we're venturing into the realm of metaphysics here.

I do shrug off the "stone too big for God to lift" because that dilemma has been reasonably dealt with hundreds of years prior. Omnipotence does not demands illogicalness. If you created a non-math problem, such as "what's the square root of yellow" and gave it to the best mathematician in the world, you would not question his mathematical prowess if he said that formulation of the question was illogical, such that he was unable to answer it.

As far as "evidence" for God's "boundedness" by logic, you'll see that arguments are exactly the evidence in the offing. What would I do otherwise? Run a lab-based experiment? The whole point is NOT that God is "bound" by logic but that OUR inquiry into God's nature is rendered unintelligible if we ask illogical questions. Does that make sense to you?

29 December 2015 at 11:45 am

Yes, it makes perfect sense that you can't provide evidence. It would have been great if you could have, but I am not surprised in the least.

Also, "the square root of yellow" is a different kind of non-sequitor than "being able to create a stone so haveavy that he couldn't lift it"

One is impossible because the words don't relate to each other, whilst the other shows the impossibility of a certain property, in this case omnipotence.

Here's something else;

If God's omnipotence is not harmed by not doing evil, then how is human free will (if you believe in that, which I don't) harmed by not doing evil?

29 December 2015 at 8:02 pm

As much as I don't really feel like countenancing this bizarre and self-refuting "evidentialism" you seem to be forwarding, I feel it's worthwhile to point out that logic, indeed, is evidence. Without logic and arguments, we cannot even support evidentialism itself, hence the self-refutation.

Moreover, if something is by definition not empirical, why in the world would we demand empirical evidence to support claims of its existence? Think of all the great philosophical debates: realism v. anti-realism, free will v. determinism, deontology v. consequentialism, something rather than nothing, indeed, even atheism v. theism. These matters might be aided by empirical evidence, but empirical evidence is far from the outward limit of these inquiries and can stifle them if we draw (again, self-refuting) boundaries about what kind of "evidence" we will admit. Narrowing the field of what constitutes evidence (an approach favored by quite a few atheist pundits) only narrows what we are able to say about the world.

You're right in saying that the example I produced is a different kind of non-sequitor. However, both of the formulations remain non-sequitor. One might as well ask the best mathematician in the world to create a differentiable, continuous function which derivative he cannot find at some point. We would not doubt his mathematical prowess if he couldn't do so, because this feat is logically impossible and hence a non-task (think of the parallel: "making a math problem [of a knowable mathematic form] so hard that he can't solve it" [note: I'm not talking about math problems that are "knowably unsolvable" here, such as those from Hilbert's problems]). Sematics aside, we can see that this little rock example is more or less a red-herring; not only is it formulated in a way that is not intelligible (as a paradox), it also does not pertain to the pressing matters of theology; that is, its form is unintelligible and its content is trivial. This isn't of course to say that your questioning of the concept of omnipotence is unwarranted. However, we must recognize that this particular example has been dealt with quite thoroughly.

To your question regarding human free will and the capacity to do evil, I would say simply that because God is BOTH omnipotent and omnibenevolent, it would constitute a violation of God's nature to do evil. It has less to do with God's freedom and more to do with God's nature, in other words. However, human beings are not omnibenevolent, so they remain with the capacity to do evil. It is part of human nature to be able to choose between good and evil. If we lacked that, we would not exactly be human.

Now, it seems like the concern that lies behind your question, though, is whether God could have created a world in which humans always independently choose good. This is sort of in the realm of Frankfurter style experiments involving free will, if you are familiar with those. It seems to me that such a world of humans constantly choosing only good, however, would not allow for virtue and development — we would make no (moral) mistakes and morality would in effect be as trivial as the functioning of the autonomous nervous system. I very much hope that the world comes to a point in which everyone independently chooses to do good, but were that the case from the beginning there would be no moral development to speak of.

29 December 2015 at 8:20 pm

If anything you just showed why omnipotence and omnibenevolence are incompatible.

In order to be omnibenevolent, one has to be unable to do bad, which means that omnipotence is not possible.

Regarding free will;

Why is moral progress even necessary? It sounds like you're saying that development is necessary, but I'd like to know why. What would be so bad about a world where no one would do bad things to begin with?

The only reason that morality is so valued is specifically because people have done and continue to do bad deeds. If we didn't do bad things, morality wouldn't be necessary any more.

In other words, it sounds like you're putting the cart before the horse.

29 December 2015 at 9:55 pm

Hmm… I'm not quite sure how you're understanding omnipotence, but I don't think you addressed my mathematician example. I don't think an omnipotent being "has to do anything". Perhaps we are confusing "possibility" with "actuality" here. Insofar as God is an omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient being, God is clearly different from a being that is ONLY omnipotent. But it seems like the whole idea here is that we don't understand God to be ONLY omnipotent. Also, it might be worth considering what God's omnipotence actually means existentially for human beings. That's kind of what I'm getting at when I say the stone example is trivial in its content.

"The only reason why morality is so valued is specifically because people have done and continue to do bad deeds." So, do you think morality is only prohibitive? I thought your point from the start was that people do good things for "goodness sake." Good acts are good regardless of whether bad acts happen, but that doesn't mean that we don't have to learn how to do good through making moral mistakes (nor does it mean that good acts are not made meaningful by the POSSIBILITY of bad acts). I think morality very much would continue to be important even if people stopped doing bad things because the draw to do bad things would still exist. Doing good takes effort. That's why integrity is such an important thing. Plenty of other virtues like that need to be learned. If they're inherent, if there is no struggle and cost of doing them, no sacrifice, then they aren't terribly virtuous anymore. They're just automatic modes of functioning.

In short, I'm just a little perplexed by your moral sensibility. From St. Augustine through the Scholastics to Enlightenment philosophers (especially Kant) the developmental aspect of morality has been crucial. I mean, is there any point in just be handed an ability if you don't have to work for it? I feel like you're missing out on the entire existential side of all of this. We're not just talking optimization and syllogisms here.

30 December 2015 at 5:54 pm

A great exposee of one crazy Christian doctrine! This type of logic led me away from Evangelicalism to a more tenable version of Christianity. But it's not total nonsense:-

A ransom does not have to be paid to a scumbag. A ransom can simply be a costly payment made to free someone from some sort of bondage. In this case I don't think it was Jesus' death that was the payment, but he "gave his *life* as a ransom for many". His one precious life which he could have spent pleasing himself, instead he spent "ministering to others" and trying to rescue them from the bondage of trying to keep the Jewish ceremonial law, praying publicly, giving alms, etc. And feeling guilt-ridden because they did not do so as perfectly as the teachers of the law said they should. Specially if they once succumbed to temptation – they were forever an outcast and could never get back into God’s favour.

Jesus told them that true religion was not ceremonial but a matter of the heart, and praying and giving alms should be done in private, etc. He told them God was not a critical judge permanently noting down all their shortcomings but rather a loving father who would welcome them back and let them feel his love if they tried to please Him. This is the way in which Jesus rescued or *ransomed* the oppressed and outcast.

Just as Daniel here is spending time blogging to rescue poor souls who are in bondage to some similarly repressive religion. He is paying in time, effort and expense – a *ransom* if you like – to free others from a bondage which he once found himself to be in, way back whenever it was. If a scumbag demanding payment exists, it is the darkness and ignorance and crookedness in minds that have somehow allowed themselves to get into bondage.

You will find plenty of support for alternate theories on the atonement amongst thinking Christians. Take for instance C.S Lewis who calls this one "a very silly theory" (Mere Christianity, Bk2,Sec4), or Lewis' hero George MacDonald who wrote a whole sermon in response to Herbert Spencer's summary of it: "The visiting on Adam's descendants through hundreds of generations dreadful penalties for a small transgression which they did not commit …" (Unspoken Sermons Series 2: The Truth in Jesus). MacDonald calls this dogma "abominable" and declares his conviction that "there is not an atom of such teaching" in the New Testament!!

In fact if you look into the origins of this so-called penal substitution theory, I think you will not find anything like it in writing until at least Anselm around 1100 CE. My understanding of Anselm's idea (called the satisfaction theory) is that since Jesus bore punishment he did not deserve, Justice then owed him restitution. And the restitution he chose was that his followers be let off the punishment they deserved. This idea makes some sense, but I don’t think it has a shred of truth either.

The more modern and widely accepted penal substitution theory (which is the one dissed here) didn't get dreamed up until the reformation in the 16th century and amazingly has now largely replaced Jesus' "Gospel of the Kingdom" as being the Christian gospel. To think that what has now become the gospel wasn't even dreamed up until the 16th century, and is regarded by some good Christian thinkers as being anything from silly to outright abominable – it boggles the mind!

But I can’t help wondering about the "Witness of Jehovah". I wonder if he is another poor soul witnessing from the pressure of religious bondage who himself needs ransoming, or whether he has found a real Joy that he can hardly keep from sharing and just doesn’t know how to think clearly or talk sense about it.

31 December 2015 at 7:35 am

I'm with you on most of that, but I'm a little worried that you seem to be undercutting the more demanding features of the Christian message for what some might term a "therapeutic" Christianity in which Christians are urged to be "less hard on themselves" and have "nothing to account for." I think St. Anselm is certainly on to something in saying that humans do indeed have something to account for and exist with a fundamental need for redemption. In other words, we are not somehow self-sufficient and without need of Christ's message from the get-go. That is precisely what the Christian life is meant to transform.

31 December 2015 at 1:32 pm

Thanks for the support. I’m not sure what you mean by "the Christian message", but I take far more notice of what Jesus said than what his followers and the church said after he left. Jesus wanted his disciples to "be perfect as their heavenly Father is perfect". And he wanted their lives to show a righteousness motivated from love (as of a child pleasing its father) to exceed the righteousness of the Pharisees (which was that of a slave serving a master). So it seems they need to be pretty hard on themselves to continue their spiritual progress to this level!

But in terms of having to "account" for past misdeeds – Jesus made it plain (in a parable or two as well as in the prayer he taught) that to really feel God’s forgiveness for their misdeeds, they must undo the harm and become reconciled as far as possible, and forgive the same sort of misdeeds that others have perpetrated against them and theirs. The fact that one often "reaps what one sows" tends to ensure that misdeeds to be forgiven are of a similar nature and degree to those committed. And I don’t think the requirement ends with this life. According to the parable: one is not released to progress in the heavenly realms until one has "paid the last penny" (Matt5:26) of repentance for things others have against you from this earthly life!

As far as some Anselmian transaction existing between the gods, it seems not evident from Jesus’ teachings? And even if it did exist, it seems one doesn't have to know about it, much less believe in it, for it to still work. All the saints before Anselm (and the old testament ones in particular) seemed to have found their way into heaven without guessing any transaction existed.

2 January 2016 at 7:51 am

I guess now that what you are calling "the Christian message" is the "Jesus died for your sins" type of statement that has been so central to Christianity ever since Jesus' departure. It is a mystery that if possible needs a rational explanation. It is in search of this explanation, together with the (I think superstitious) belief that all the Bible writers were 100% correct in all they wrote that resulted in the penal substitution idea of the reformation. However looking in the NT alone for an explanation to the NT story, MacDonald (who confesses he loves the book beyond expression) finds "not an atom of such teaching". The best analogy for it that I have found is from Sadhu Sundar Singh who writes (as if spoken by Jesus):

"A rebellious son once left his father's house and joined a band of robbers and became in time as bold and ruthless as the rest. The father called his servants and ordered them to go to his son and tell him that if he would repent and return home all would be forgiven, and he would receive him into his home. But the servants, in dread of the wild country and fierce robbers, refused to go. Then the elder brother of the young man, who loved him as his father did, set off to carry the message of forgiveness. But soon after he had entered the jungle a band of robbers set upon him and mortally wounded him. The younger brother was one of the band, and when he recognized his elder brother he was filled with grief and remorse. The elder brother managed to give the message of forgiveness and then, saying that the purpose of his life was fulfilled and love's duty done, he gave up the ghost. This sacrifice of the elder brother made so deep an impression on the rebellious youth that he went back in penitence to his father and from that day forward lived a new life. Is it not right, therefore, that My sons should be prepared to sacrifice their lives in order to bring the message of mercy to those of their brethren who have gone astray and are ruined in sin, just as I also gave My life for the salvation of all?"

I think this parable explains most aspects of the event. I think Jesus makes it plain that his message was aimed at the 1 sheep out of a hundred that was really "lost" – not for the 99 "that need no repentance", and that God through Jesus was willing to go out of his way to search for the lost coin, and even lay down his life to gain back the lost sheep. That God's love reached to this level was never before revealed to mankind until Jesus. So even if there was only a very few who would be touched by his sacrifice (such as the Centurion or a robber being crucified), it would still be worth it and would be his Father's will. There is good evidence that the early church also took the view that his sacrifice was to "reconcile sinners to God" as the expression is *never* put the other way around – that God is thereby reconciled to the sinner – which would be Anselm's and the reformation's way of putting it.

This view seems to be called the moral influence theory and historically was championed for a while by a fellow called Abelard. However regardless of the real reason for Jesus' voluntary death, speaking of it in sermons has touched hearts and changed endless lives ever since Peter's first sermon at pentecost which made ~3000 converts. When something works so well, most people don't care to wonder too much about how or why it is so, but just use it for all it's worth.

3 March 2016 at 5:32 pm

Did anyone ever wonder how Jesus stayed up on that stake (as the JW believe how he died, opposed to being on a crucifix)? I’m no physicist but wouldn’t gravity prevail, him sliding on down to the ground? No philosophical discussion here, just pragmatic questioning!