Richard Dawkins is Richard Dawkins. His talk was entitled “Now Praise Intelligent Design”.

Intelligent design gets a bad rap, you know. The term’s been sullied to the point where it’s been described as ‘creationism in a cheap suit‘. But all of us rely on intelligently designed things to make our lives easier. Even Dawkins believes in intelligent design — for man-made objects, as he’s explained on Colbert.

But back to the talk. Dawkins wants us to take back intelligent design, the better to design our future intelligently. In fact, Dawkins suggests a few terms we should be taking back:

- Morality.

- Pro-life. You know who the real pro-lifers are? Médecins Sans Frontières, that’s who.

- Spirituality. The feeling of transcendence at seeing the night sky is available for all of us. (Personally, I never use the term ‘spirituality’ because it’s so vague and easy to misunderstand, and I don’t want to dignify it with anything important, but that’s me.)

- Christmas. Christians are only the latest to put their stamp on the set of pagan festivals surrounding the Winter Solstice.

And, of course, intelligent design. Dawkins explained that brains and computers are the only things capable of intelligent design, and they have origins that we know and understand. It used to be that people thought that if something looked designed, it was designed. Then Darwin showed how evolution by natural selection could create things that were apparently designed. Dawkins calls this ‘neo-design’, and differentiates it from ‘paleo-design’. Evolution (paleo-design) created us, and now we create things (neo-design).

Unfortunately, says Dawkins, paleo-design is often bad design, as evidenced by the recurrent laryngeal nerve in giraffes. This nerve takes a long path down the neck, only to connect a few centimetres from where it started. The long trip was necessary because that nerve had to work in every giraffe throughout generations of evolution, so as necks got longer, the nerve had to stretch. No intelligent designer would design a giraffe this way (nor would it give us back-to-front retinas), but evolution would. It has no plan for the future. Neo-design does, but even then we can hit problem when designing big things like a society — we sometimes lack the political unanimity to carry out a solution.

Can our morality be designed and if so, how do we design it? Dawkins seemed to relish this part, as he threw out some (perhaps half-warmed) red meat to the crowd. The idea that we should get our morality from the Bible is, in Dawkins’ words, “a sick joke”. It says “Thou shalt not kill” (which anyone could work on their own), but then Moses kills 3,000 people. The New Testament isn’t much better: God couldn’t think of a better plan than to come down as his alter ego to be horrifically tortured and killed to atone for the sin of Adam (who never existed) so that he could forgive himself.

And yet, for many people, morality and religion have a very strong mental link. When the RDF commissioned a survey into people’s responses on the census, they asked people why they’d ticked the “Christian” box (that’s 54% of the total), and many responded “Because I like to think of myself as a good person.” Yet when asked “When faced with a moral dilemma, do you turn to your religion?”, only one tenth of the 54% said yes. The bulk of the 54% said they looked to their innate moral sense. Even this doesn’t tell the whole story. Inescapably, we get our morals from the time in which we live. Darwin and Huxley were oppsed to slavery, but they would have been considered reactionary and racist by today’s standards.

Dawkins then launched into a discussion of some gray areas of morality. What about euthanasia? An absolutist might offer a blanket condemnation, but a consequentialist could point out that, if prolonging life is the goal, then legal euthanasia might prolong life. How? A number of people kill themselves while they’re able to, knowing that when they become incapacitated, they wouldn’t be able to, and no doctor would be allowed to help them.

What about eugenics? asked Dawkins, and I detected a tension in the audience. After all, eugenics is something religious people hurl at us when we talk about designing our own morality. So what about it? Yes, we condemn the idea of manipulating genes to engineer ‘superior’ humans, but most people are okay with negative eugenics, that is, testing a cell for a bad gene. What’s the difference between this and positive eugenics, say, for having a blue-eyed child, or a child who is a great musician? Even Dawkins said this was farther than he wanted to go, but then pointed out that most people mould children by non-genetic means — not by manipulating genes, but by forcing the child to practice the piano for hours a day. It’s anyone’s guess as to which is more cruel, thinks I, glibly.

Dawkins finished with a discussion of how religions evolve and survive. What’s the mechanism?

1. Is it that religious people are healthier, and this helps regions to propagate?

Dawkins says the evidence for this is sketchy, and that he only mentioned it for completeness.

2. Does religion spread by piggybacking on useful things?

For example, children are susceptible to indoctrination, and that’s a good thing because accepting things that adults say gives children knowledge that helps them to survive. Religion, however, exploits this feature of childhood in parasitic fashion.

3. Does religion help groups survive?

Dawkins describes group selection as ‘silly’, but allows that some groups might have attributes that help them survive better than others. Even so, says Dawkins, that’s not proper group selection.

4. Could the question have a memetic answer?

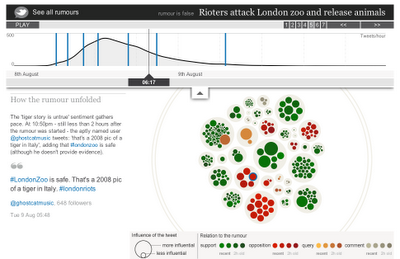

Memes (or ideas) spread quickly throughout a population, and remain robust despite opposition. As an illustration, Dawkins showed this graphic of the London tiger rumour as it progressed through time, all tracked through Twitter. Click to go to the interactive graphic — it’s really interesting. It’s like doing an epidemiology of rumours.

Overall, good talk, with a lot of diverse foci. I’m interested to see what he gets into next.

12 May 2012 at 8:24 pm

The words intelligent and design never appeared in the same sentence until the Christian Creationist Discovery Institute began selling it as scientific idea while knowing it's just a childish religious fantasy.

When Dawkins uses the same code words, intelligent design, he is inviting dishonest quote mining. Not a good idea Mr. Dawkins.

http://darwinkilledgod.blogspot.com/

12 May 2012 at 11:43 pm

Interestingly, the term 'intelligent design' has been used since the 1800s

http://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=intelligent+design&year_start=1700&year_end=2008&corpus=0&smoothing=3

but always in a religious context. I certainly don't have any enthusiasm for taking it over. I think Dawkins was trying to subvert their frame, but probably not very successfully.