Michael R. Ash is continuing his discussion of testimony over at the Mormon Times with a column titled “What critics don’t understand about testimony“.

Don’t understand testimony? What’s not to understand? I’ve had one and recovered. One thing I wish Mike Ash understood is that testimonial evidence is not good evidence, and relying on it is asking to be fooled.

He’s making an assumption here is that critics of the church don’t understand the church. (It’s a bit like the soggy drunk in a bar, saying “My wife doesn’t understand me.”) Many of us used to be LDS. Some of us served in the church for years, had a testimony, and remember the feelings that kept us believing with more certainty than was warranted by real evidence. So another thing I wish Mike Ash understood is that we do understand the church. We’re critical of the church because we understand it.

While a testimony must be grounded on a spiritual confirmation, the mind is an integral part of gaining our testimony. We are expected to use our minds to study the scriptures and learn what God wants.

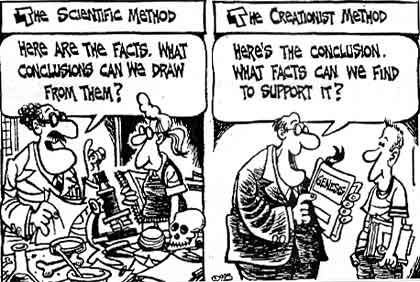

Whoops, presupposition. Whether a god exists is one of the items still under consideration for the testimony-hunter. So the next thing that I wish Mike Ash understood is that if you start from your conclusion, and then try to amass facts to support it, you’re doing it wrong.

When Oliver Cowdery made his failed attempt at translating the plates the Lord told him: “Behold, you have not understood; you have supposed that I would give it unto you, when you took no thought save it was to ask me. But, behold, I say unto you, that you must study it out in your mind; then you must ask me if it be right, and if it is right I will cause that your bosom shall burn within you; therefore, you shall feel that it is right.”

It’s true that Mormon writings encourage you to think about things that you’re praying about. But encouragement to think does no good unless you learn how to think well — another thing Ash doesn’t seem to understand. That’s not an insult to any Latter-day Saints. Thinking well is a skill. No one’s automatically good at it, and everyone is bad at it when cherished beliefs are on the line. Including me — I’m not nearly as critical of ideas I agree with as I ought to be. But by learning only a few things about how to spot a fallacy and how we fool ourselves, the poor reasoning at church becomes easy to spot.

Here’s a good example:

In 2007, the church published a statement about LDS doctrine which read in part:

“The church exhorts all people to approach the gospel not only intellectually but with the intellect and the spirit, a process in which reason and faith work together.”

It’s no surprise that the church tells people that faith and reason work together. Magical thinkers have been borrowing the credibility of science for years. It’s just a way of muting concerns: Gee, if the leaders say that reason is good, then this testimony thing must be scientifically valid after all. But while reason is concerned with logic and evidence, faith encourages belief without evidence. You can’t use both at once. Faith and reason are opposite and incompatible methods. And that’s another thing I wish Mike Ash understood.

3 April 2011 at 3:27 am

Huh, well it appears that nobody really understands it. Obviously the critics don't get it [eye roll]. But even the members don't either. About how often are lessons repeated in Sunday School and at Conference?

4 April 2011 at 2:39 am

Sometimes I think people are so scared of "thinking" and using scientific methods to analyze and critique. This is especially true in churches and religions where people have lost their identity by devoting so much. This means that these people are unlikely to critique their religion.

22 November 2013 at 6:27 pm

I appreciate this post Dan.

"faith and reason are opposite and incompatible methods."

This implies that doubt and reason are compatible.

Yes, every substantial objective claim about the world should be confronted with doubt, or at least a "methodological" doubt if one is honest about honoring truth. Adding "methodological" as a qualifier recognizes that it is also human to be disposed toward wanting/hoping certain things to be true (or false) from the outset, but that must not be confounded with evidence.