Last week saw the passing of Martin Gardner, a mathematician, skeptic, and puzzle master.

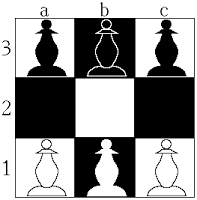

I first became aware of his work when I was just a wee lad, probably about nine. I ran across an article he wrote about ‘Hexapawn’, a game he invented. Hexapawn uses only six pawns, on a 3 x 3 board, like so.

You can move like a pawn in chess: straight ahead, or diagonal to capture. You win either by getting to the last rank, by capturing all the other player’s pieces, or blocking the other player so they can’t move.

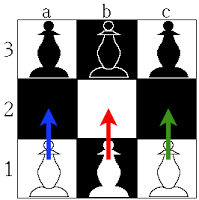

The article showed diagrams of all the possible moves in the game, in the form of pictures like this one.

You were meant to print these out, paste the pictures onto matchboxes, and put coloured beads in the matchboxes. When you’d done this, what you had was a kind of computer. You’d make your move, look at the board, choose the matchbox that matched the current state of the board, shake up the matchbox, and the colour bead you pulled out was the move the computer would make. If that move made the computer lose, you would remove that bead so the computer couldn’t make that move anymore.

Eventually, once all the losing moves were pruned out of the system, you’d have an unbeatable Hexapawn machine. This was my introduction to machine learning and AI. What an eye-opener! I realised that unthinking boxes (or computer chips, or what have you) could learn things without people explicitly teaching them.

(Here’s an implementation of Hexapawn as a PDF.)

Later, I found a book called “Mathematical Puzzles of Sam Loyd“, which Gardner edited. I spent hours poring over Loyd’s puzzles, and Gardner’s explanations. Later I picked up Gardner’s “My Best Mathematical and Logic Puzzles“.

Gardner was a skeptic, but he believed in a god. Here’s a bit from an interview with Michael Shermer in 1997.

Skeptic: Inevitably skepticism leads to asking the God question. You call yourself a fideist.

Gardner: I call myself a philosophical theist, or sometimes a fideist, who believes something on the basis of emotional reasons rather than intellectual reasons.

Skeptic: This will surely strike readers as something of a paradox for a man who is so skeptical about so many things.

Gardner: People think that if you don’t believe Uri Geller can bend spoons then you must be an atheist. But I think these are two different things. I call myself a philosophical theist in the tradition of Kant, Charles Peirce, William James, and especially Miguel Unamuno, one of my favorite philosophers. As a fideist I don’t think there are any arguments that prove the existence of God or the immortality of the soul. Even more than that, I agree with Unamuno that the atheists have the better arguments. So it is a case of quixotic emotional belief that is really against the evidence and against the odds. The classic essay in defense of fideism is William James’ The Will to Believe. James’ argument, in essence, is that if you have strong emotional reasons for a metaphysical belief, and it is not strongly contradicted by science or logical reasons, then you have a right to make a leap of faith if it provides sufficient satisfaction.

It makes the atheists furious when you take this position because they can no more argue with you than they can argue over whether you like the taste of beer or not. To me it is entirely an emotional thing.

This is strange to me, but it’s not the first time I’ve seen a good reasoner suspend critical thinking in favour of supernaturalism. And emotional reasoning is a terrible rationale — it’s like saying ‘I’m going to believe it if it makes me feel satisfied.’ Oh, well, good for you. This is epistemological hedonism.

And it gets the reasoning backward. Gardner argued that you could believe what you liked if it wasn’t strongly contradicted by evidence, but we’ve already seen that when someone’s in the grip of a belief, no evidence is ever strong enough. Science works the opposite way: you believe something when there’s evidence to support it.

On the other hand, Gardner sounds like someone who’s done the reading (unlike me) and knows his way around the philosophy. He’s aware that his position is reaching out into the unknown, and even though he chooses to believe, he knows that he doesn’t know.

Martin Gardner must have been a fascinating guy, exerting an influence on mathematics, skepticism, and philosophy. I’m glad I’ve had the chance to benefit from his work.

26 May 2010 at 4:38 pm

As a fideist I don’t think there are any arguments that prove the existence of God or the immortality of the soul. Even more than that, I agree with Unamuno that the atheists have the better arguments. So it is a case of quixotic emotional belief that is really against the evidence and against the odds.

That describes exactly what I used to do, how I thought about my belief for the last few years I clung to it. I wonder how common it is. I thought most apologists must do it, but I've come to understand that at least some (many? most?) actually don't recognize how much the evidence and the odds are against what they believe.

27 May 2010 at 2:04 am

You said that Science works the opposite way: you believe something when there's evidence to support it.

In rigorous empirical science you don't need to believe anything. You hold a set of unrejected theories and conjectures. You reject them when you have contradictory evidence. Theories are only 'supported' insofar as they're not rejected, all you can say is that you favour some according to parsimony, refutability, instrumentalism etc.

Relativity isn't nearly as parsimonious or testable as Newtonian mechanics, but what if someone in the 1600s had believed in it (without the equipment to distinguish it from NM)? Gardner's philosophy (if you represented it accurately) is consistent with Science, perhaps more rigorously so than believing empirical evidence can "support" a hypothesis in any way other than falsification.

27 May 2010 at 8:12 am

You hold a set of unrejected theories and conjectures. You reject them when you have contradictory evidence.

Right, and the hypothesis that I'm holding is the null hypothesis. And I see no evidence that would require me to overturn it in favour of a deity. So, provisionally, I accept the 'no god' explanation.

Gardner's philosophy (if you represented it accurately) is consistent with Science

No. From what I've quoted, I think Gardner would have been the first to admit that he didn't have the goods. He believed because he wanted to.

The 17th C person who rejected relativity would have been right to do so, on the basis of the evidence available at the time. A good many things may be true, but that doesn't mean we accept them in case evidence turns up for them one day.

28 May 2010 at 1:42 pm

I must have been reading Martin Gardner at a similar age because I actually made a hexapawn machine – right down to the matchboxes and coloured beads!!! What a nerd. Why the thought experiment wasn't enough for me I don't know.

2 June 2010 at 2:20 am

Daniel, I don't know where you learned science but I think we have different understandings of what's involved.

The 17th C person who rejected relativity would have been right to do so, on the basis of the evidence available at the time.

No! To reject anything there must have been evidence to the contrary. What null hypothesis would he have rejected? With what evidence that was available at the time (I'm assuming Newton didn't happen to conduct unpublished QM experiments)? Failing to reject the null of NM vs the alternate of relativity (type II error) is very different from rejecting relativity (type I error). Surely you understand the latter is much worse and is what science attempts to guard against?

2 June 2010 at 3:36 am

Okay, let me re-write that.

The 17th C person who xxxrejected relativityxxx failed to reject NM would have been right to do so, on the basis of the evidence available at the time.

Is that better? You do realise that the net effect is the same.

2 June 2010 at 5:45 am

Much better! 🙂

Science pedantry FTW; sorry if I sounded a bit ad hominem before.

I don't think the nett effects are equivalent but that's more a semantic viewpoint; pragmatically I can see how the consequences are similar. Having failed to reject either NM or relativity, that same scientist should rightly have favoured parsimony.